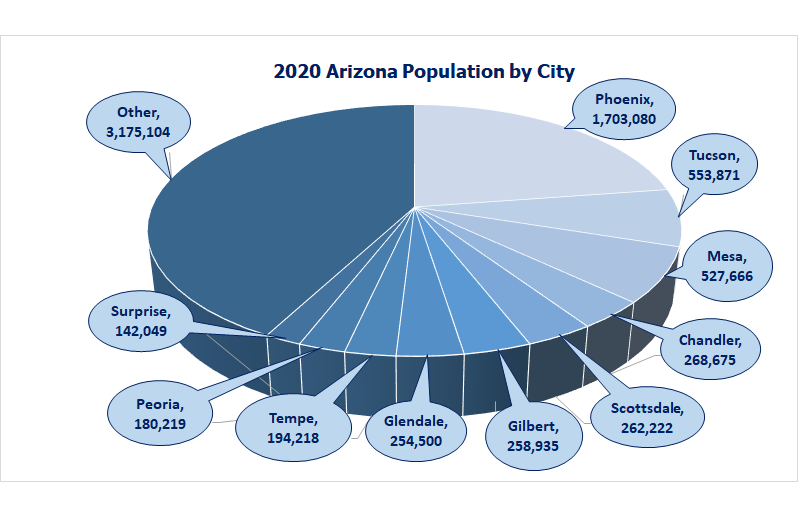

Over the last 40 years, Arizona's population has increased by about 4 million residents.[2]

Arizona's water utilities and organizations have made great strides in water conservation since the 1983 report.

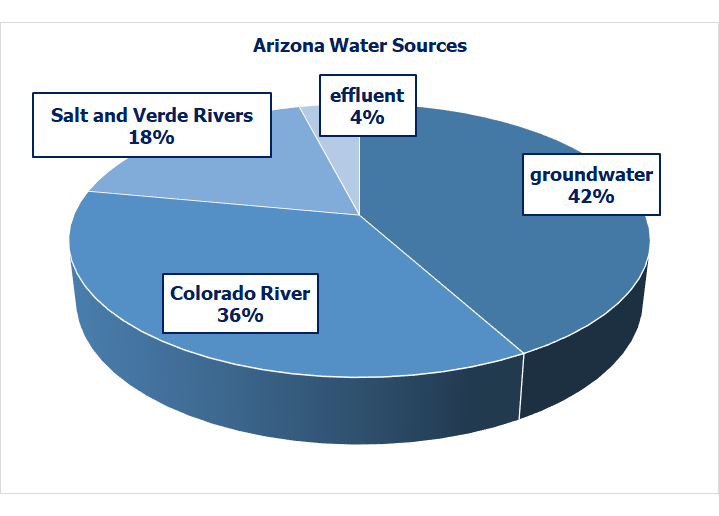

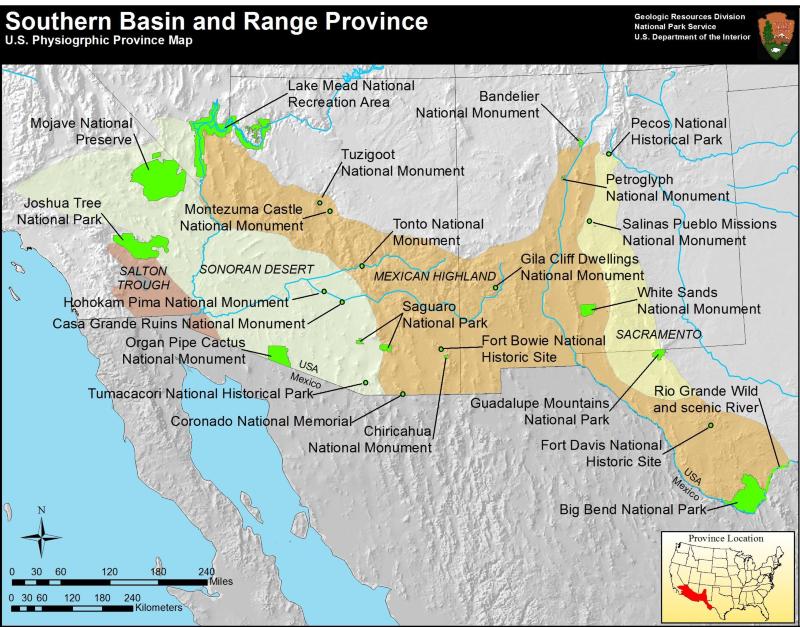

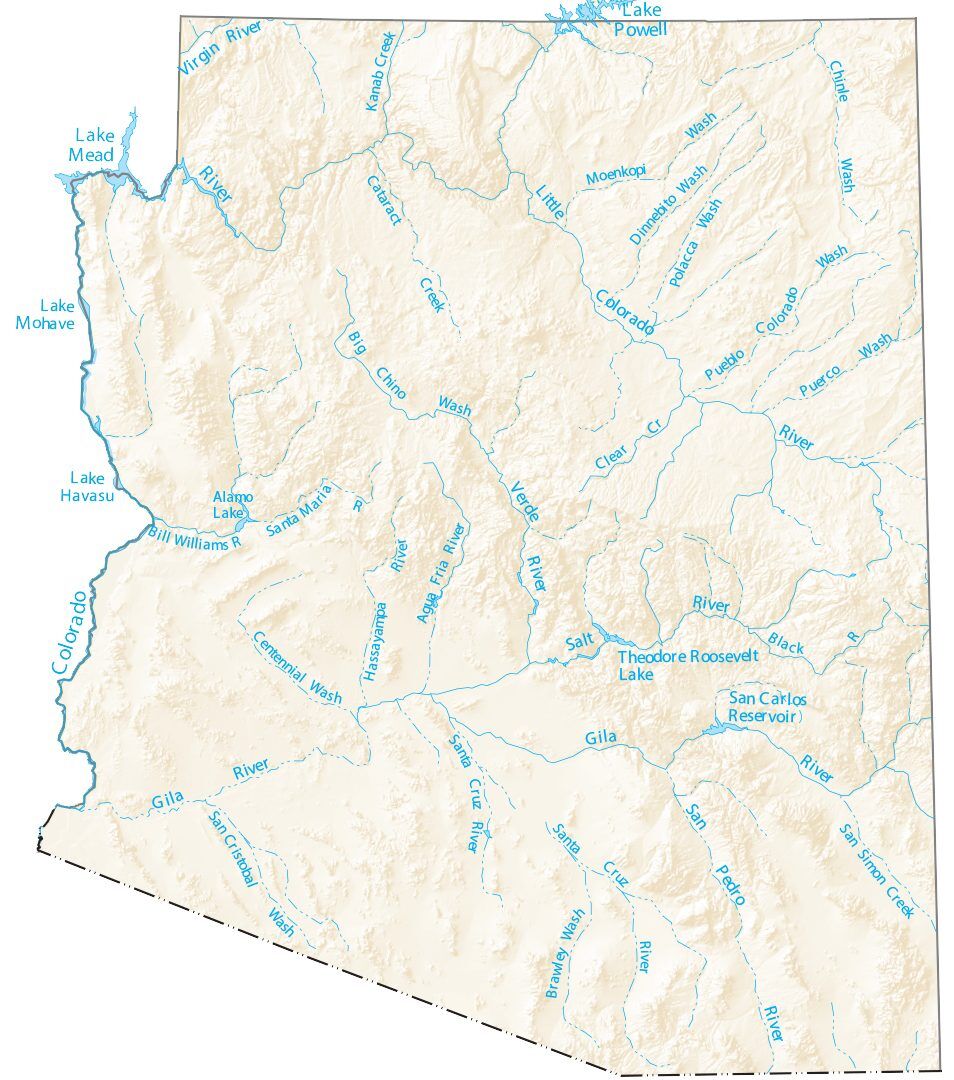

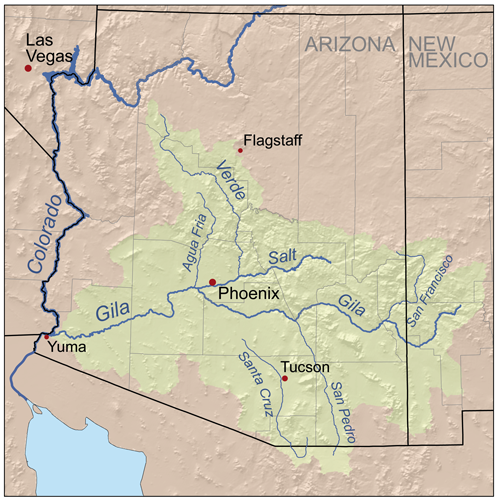

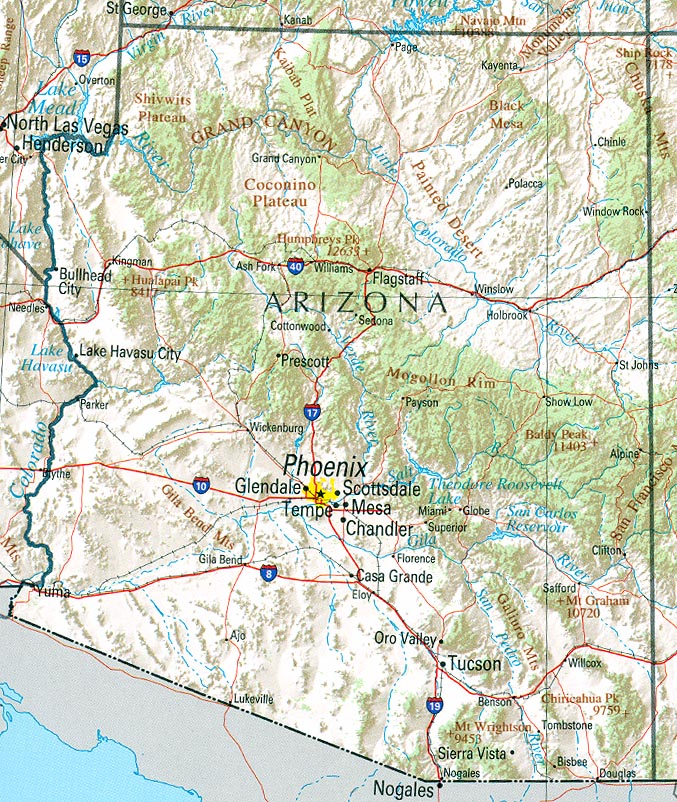

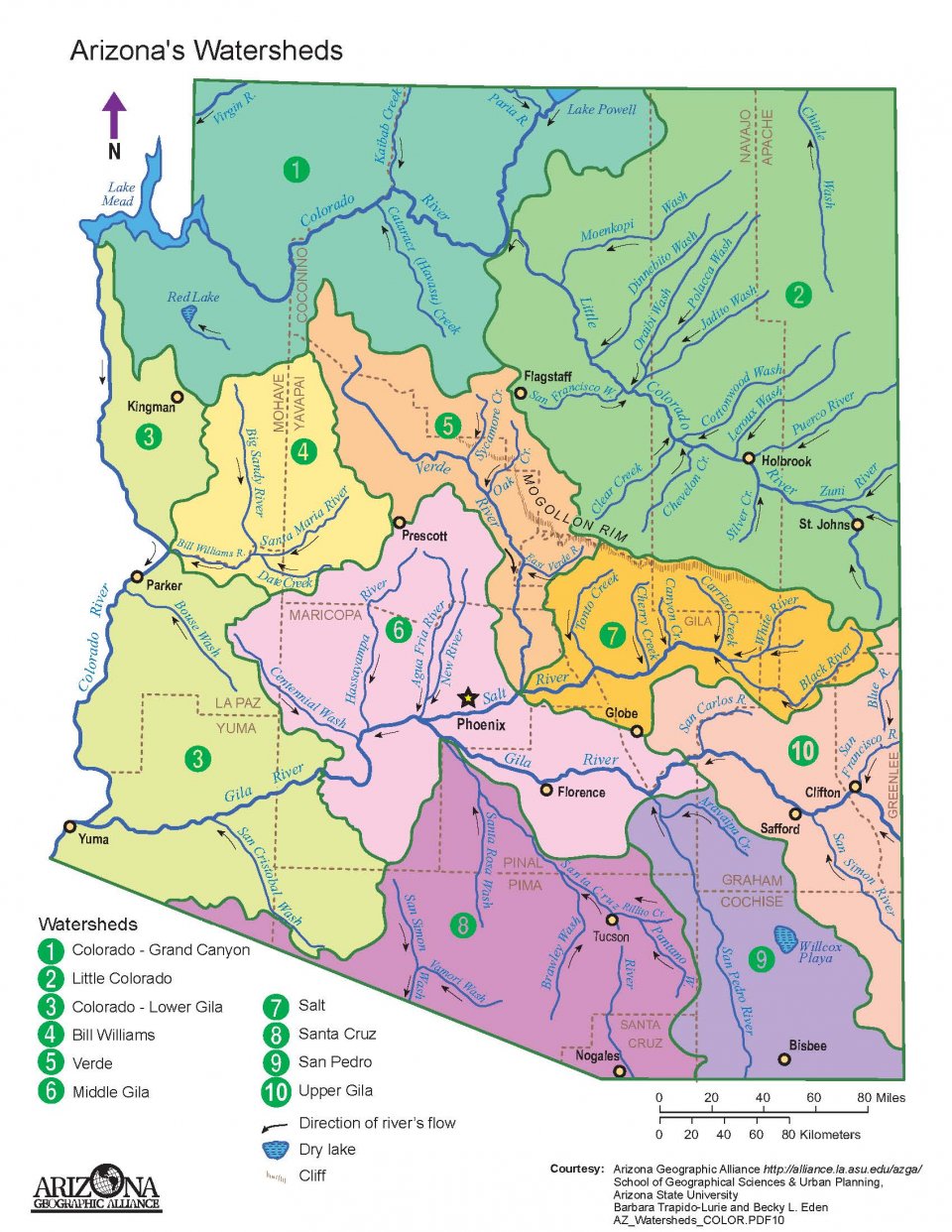

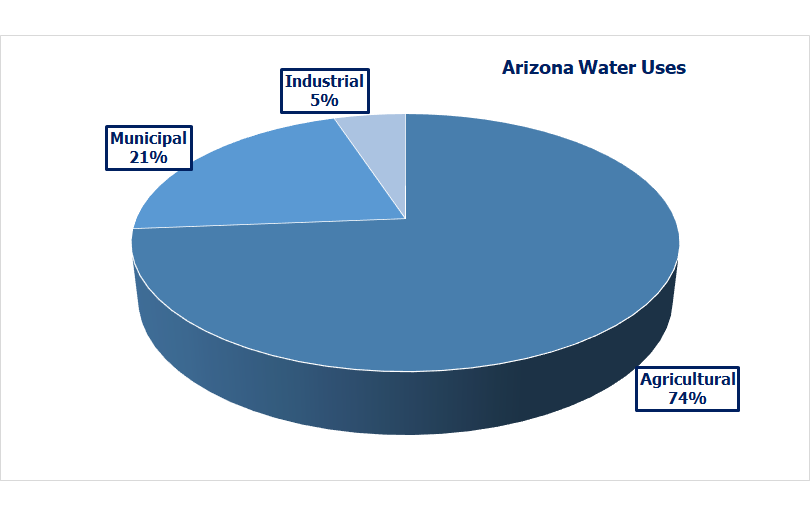

About 42% of Arizona's water use comes from groundwater, 36% from the Colorado River, 18% from in-state rivers,

including the Salt and Verde and 4% from high-quality treated wastewater called effluent.[3]

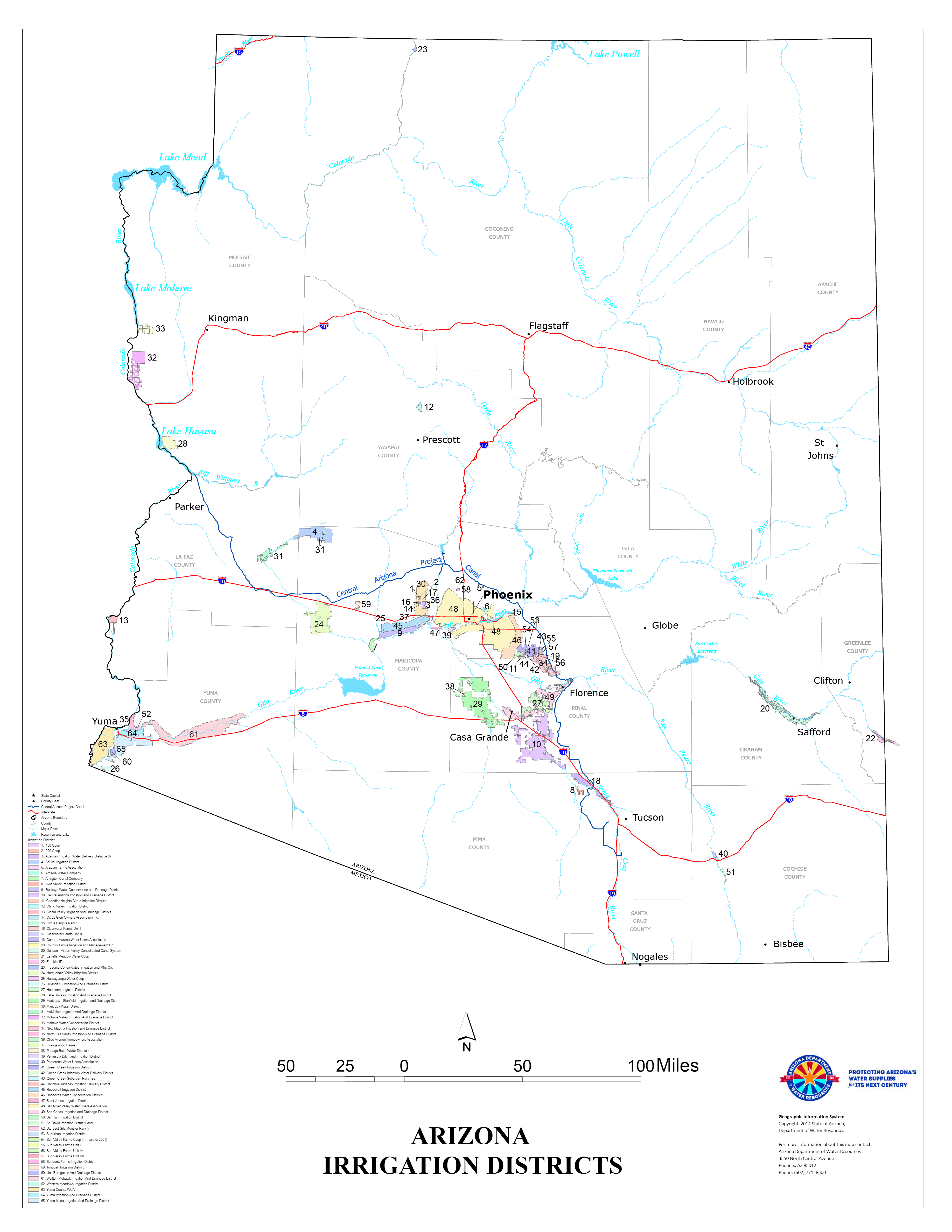

Water resources have been managed primarily by the

Salt River Project (SRP), the Central Arizona Project (CAP) and water utilities in the Phoenix

and Tucson metropolitan areas.

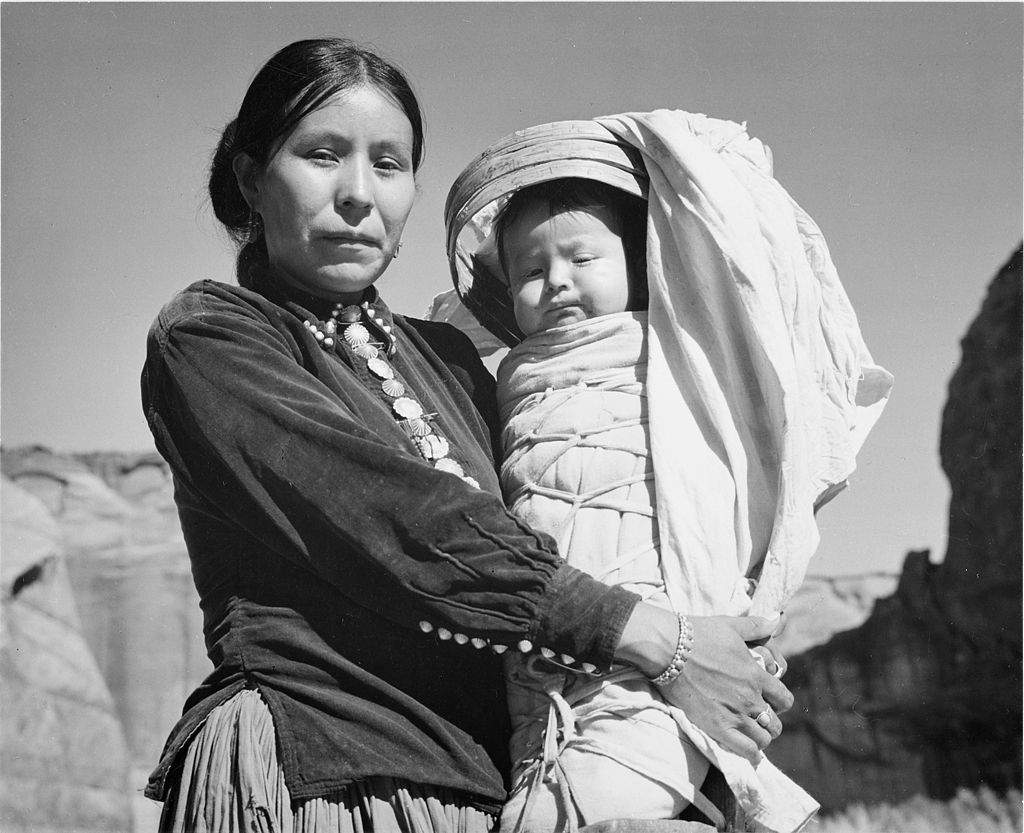

Their geographic domains, business structures and relationships with Arizona's Tribes have been shaped by more than 150 years of evolving

federal and state laws and regulations.

Sources:

[1]

Stockton, C. W. (Jul. 1983). Final report submitted to the National Science Foundation:

Projected effects of climatic variation upon water availability in Western United States. Laboratory of Tree Ring Research. University of Arizona.

https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/303523/ltrr-0048.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[2]

Country Economy. (n. d.). Arizona - population.

https://countryeconomy.com/demography/population/usa-states/arizona

[3]

Paul, H. (Oct. 2, 2018). 10 things you should know about Arizona's Groundwater Management Act. Audubon Society.

https://www.audubon.org/news/10-things-you-should-know-about-arizonas-groundwater-management-act

Over the last 40 years, Arizona's population has increased by about 4 million residents.[2]

Arizona's water utilities and organizations have made great strides in water conservation since the 1983 report.

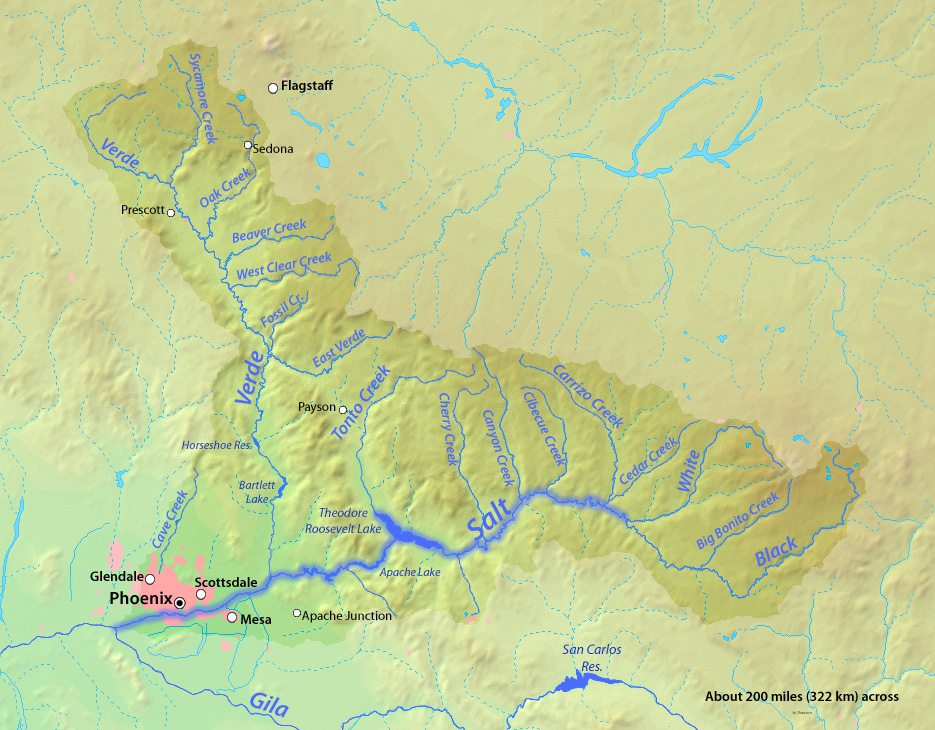

About 42% of Arizona's water use comes from groundwater, 36% from the Colorado River, 18% from in-state rivers,

including the Salt and Verde and 4% from high-quality treated wastewater called effluent.[3]

Water resources have been managed primarily by the

Salt River Project (SRP), the Central Arizona Project (CAP) and water utilities in the Phoenix

and Tucson metropolitan areas.

Their geographic domains, business structures and relationships with Arizona's Tribes have been shaped by more than 150 years of evolving

federal and state laws and regulations.

Sources:

[1]

Stockton, C. W. (Jul. 1983). Final report submitted to the National Science Foundation:

Projected effects of climatic variation upon water availability in Western United States. Laboratory of Tree Ring Research. University of Arizona.

https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/303523/ltrr-0048.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

[2]

Country Economy. (n. d.). Arizona - population.

https://countryeconomy.com/demography/population/usa-states/arizona

[3]

Paul, H. (Oct. 2, 2018). 10 things you should know about Arizona's Groundwater Management Act. Audubon Society.

https://www.audubon.org/news/10-things-you-should-know-about-arizonas-groundwater-management-act

Colorado River water management is governed by a complex system of international treaties, interstate compacts and Supreme Court decrees

which began in 1922 with the Colorado River Compact.[8]

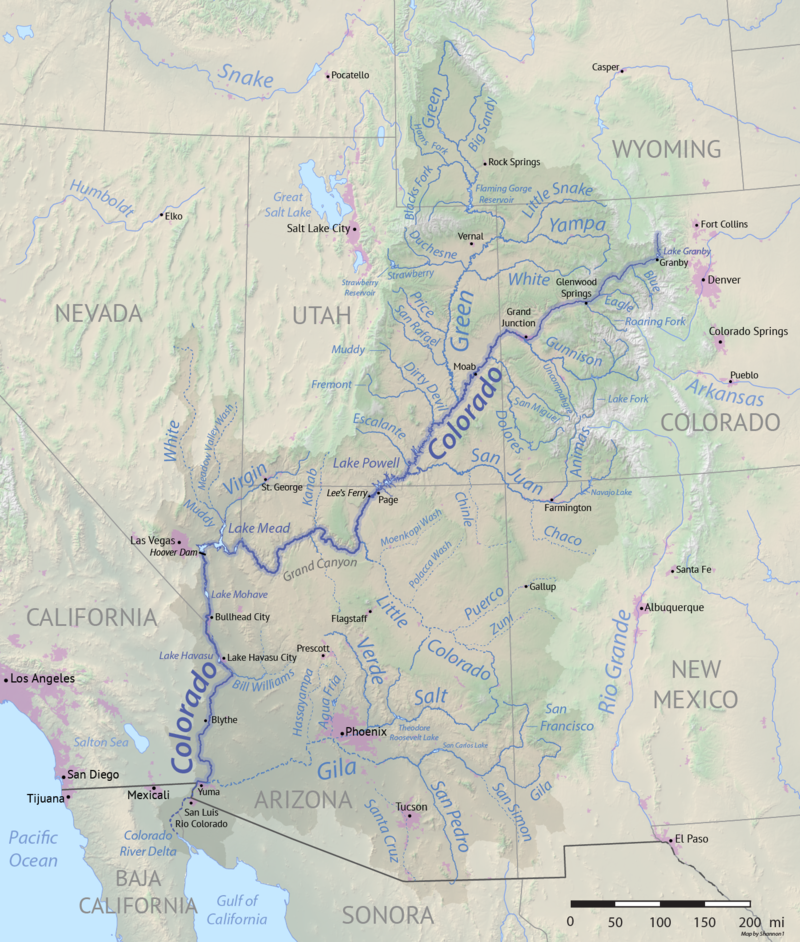

The Colorado River is about 1,450 miles long.

The headwaters of the Colorado River are located in Rocky Mountain National Park near Grand Lake, Colorado.[17]

It is about 1,450 miles long and flows across the international border into Mexico.

The drainage basin area is about 246,000 square miles and includes all of Arizona and parts of California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming.[1]

The river system supports $1.4 trillion of the annual U.S. economy and 16 million jobs, about 1/12 of U.S. domestic product.

Without Colorado River water Arizona's gross state product would drop by more than $185 billion per year and the state would lose more than 2 million jobs.[16]

For every 1 Co temperature rise Colorado River flow has decreased by 9.3%,

a depletion of 1.5 billion tons of water lost to evaporation or lack of melting snowpack.[16]

In addition to temperature changes dust may also control the speed at which spring snowmelt feeds the headwaters of the Colorado River.

More dust correlated with faster spring runoff and higher peak flows because dust-covered snow is darker and absorbs more heat than white snow.[18]

Windblown dust has increased in the Southwest due to climate change and human land-use.

As rainfall decreases protective soil is removed exposing bare soil.

Winter and spring winds pick up the dusty soil and drop it on the Rockies to the northeast at an annual rate of about five times higher

than in the mid-1800s.[18]

The major tributaries of the Colorado River, from northeast to southwest, include the Green, Dirty Devil, Escalante and San Juan Rivers.

The Green River also has several major tributaries (from northeast to southwest) including the Uinta, White, Willow Creek, Price and San Rafael Rivers.[2]

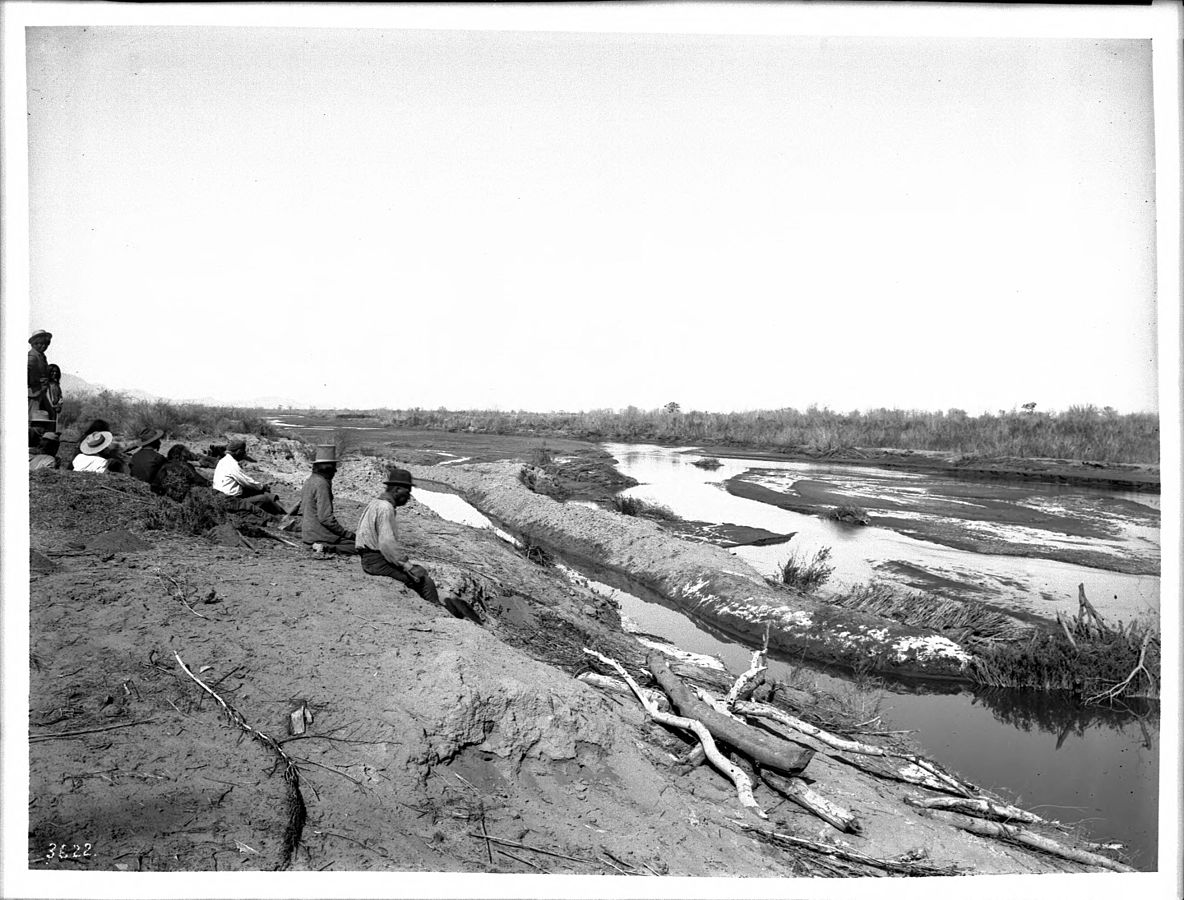

The Colorado River used to flow into a marsh in the

Gulf of California.

Colorado River water management is governed by a complex system of international treaties, interstate compacts and Supreme Court decrees

which began in 1922 with the Colorado River Compact.[8]

The Colorado River is about 1,450 miles long.

The headwaters of the Colorado River are located in Rocky Mountain National Park near Grand Lake, Colorado.[17]

It is about 1,450 miles long and flows across the international border into Mexico.

The drainage basin area is about 246,000 square miles and includes all of Arizona and parts of California, Colorado, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming.[1]

The river system supports $1.4 trillion of the annual U.S. economy and 16 million jobs, about 1/12 of U.S. domestic product.

Without Colorado River water Arizona's gross state product would drop by more than $185 billion per year and the state would lose more than 2 million jobs.[16]

For every 1 Co temperature rise Colorado River flow has decreased by 9.3%,

a depletion of 1.5 billion tons of water lost to evaporation or lack of melting snowpack.[16]

In addition to temperature changes dust may also control the speed at which spring snowmelt feeds the headwaters of the Colorado River.

More dust correlated with faster spring runoff and higher peak flows because dust-covered snow is darker and absorbs more heat than white snow.[18]

Windblown dust has increased in the Southwest due to climate change and human land-use.

As rainfall decreases protective soil is removed exposing bare soil.

Winter and spring winds pick up the dusty soil and drop it on the Rockies to the northeast at an annual rate of about five times higher

than in the mid-1800s.[18]

The major tributaries of the Colorado River, from northeast to southwest, include the Green, Dirty Devil, Escalante and San Juan Rivers.

The Green River also has several major tributaries (from northeast to southwest) including the Uinta, White, Willow Creek, Price and San Rafael Rivers.[2]

The Colorado River used to flow into a marsh in the

Gulf of California.

For decades, the merits of building the dam and water sustainability versus the apparent destruction of geologic wonders and changes to the canyon's flora and fauna

have been debated by water managers and environmentalists.[14]

On May 22, 2023 Arizona, California and Nevada agreed to take less water from the Colorado.

In return the federal government will pay $1.2 billion to irrigation districts, cities and Tribes related to the cutbacks.

The agreement will end in 2026.

The reductions are about 13% of Lower Colorado Basin water use, about 3 million acre-feet of water over the next three-an-a-half years.[19]

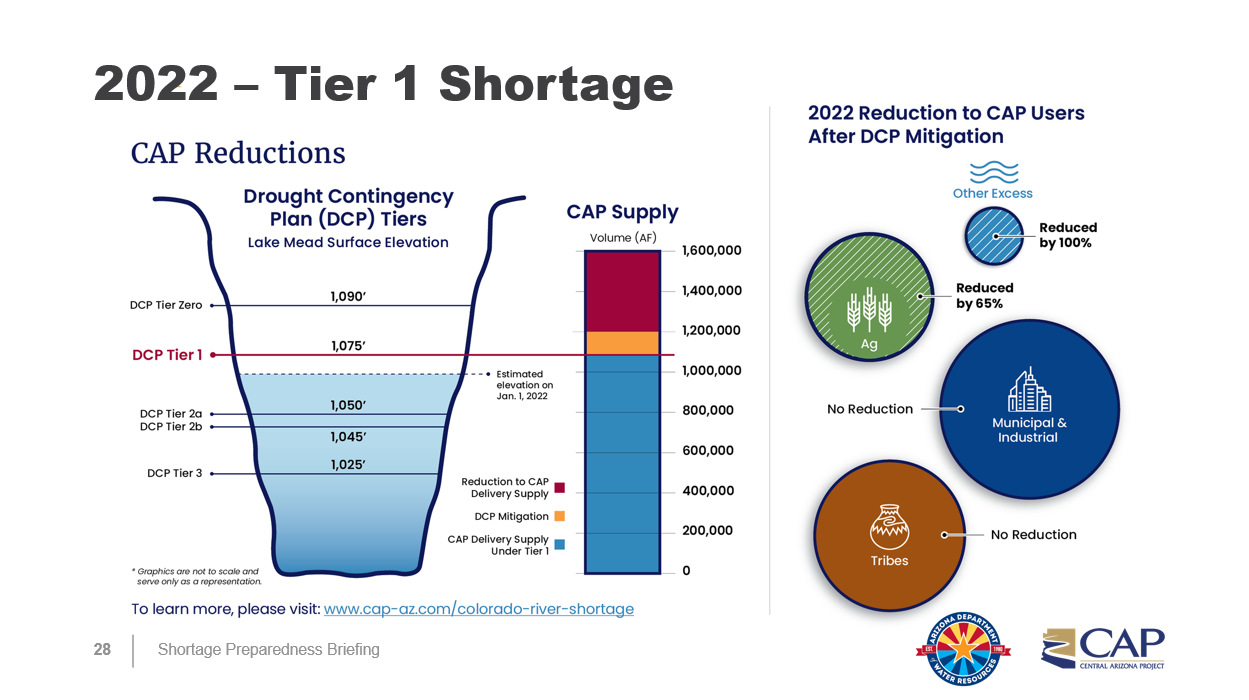

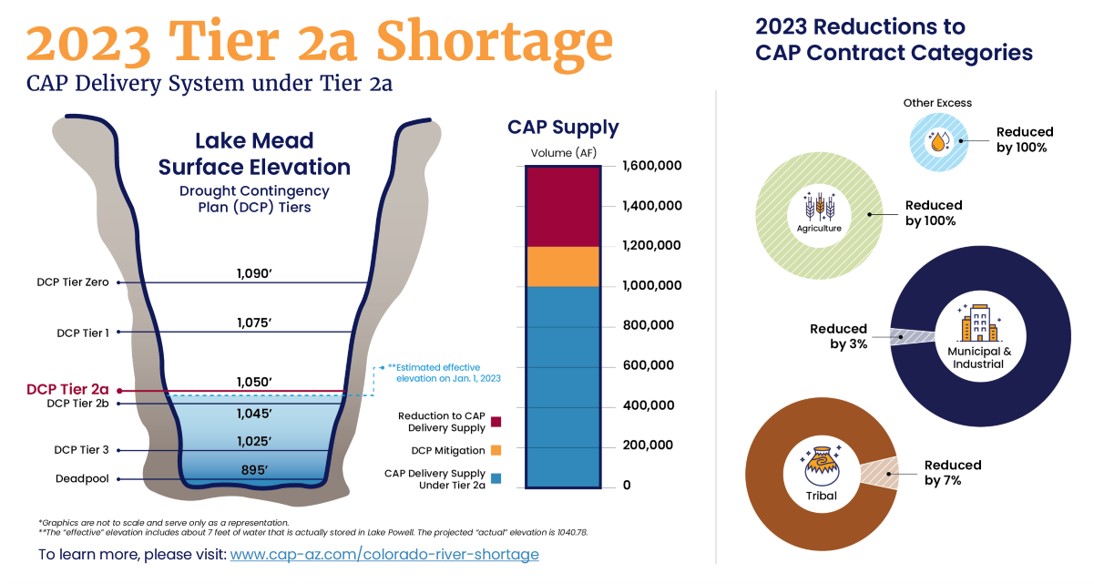

Based on the Jan. 1, 2024 projected level of Lake Mead at 1065.27 feet above sea level, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior has declared a Tier 1 shortage for Colorado River operations in 2024.[23]

On May 24, 2023, Tucson mayor Regina Romero signed a groundbreaking water conservation agreement with the Bureau of Reclamation and CAP.

Under the agreement Tucson will be one of the first Arizona cities to leave a significant allocation of Colorado River water in Lake Mead

and voluntarily conserve up to 110,000 acre-feet of water over three years.[24]

In 2023 Arizona conserved about 950,000 acre-feet, including the required 592,000 Tier 2a reduction and

an additional voluntary contribution of 355,000 acre-feet to support the Colorado River system.[25]

In a study of 2023 Colorado River data, water journalist John Fleck concluded that in the Lower Basin, Nevada's use was the lowest since 1992,

Arizona's was the lowest since 1991, and California's use may have been the lowest since the late 1940s.[27]

In the Upper Basin there appears to be an upward water use trend with substantial annual variability, but the basin is using less than its

7.5 million acre feet allotted by the 1922 Colorado River Compact.[27]

On May 9, 2024, the Department of Interior signed a new Record of Decision (ROD) to supplement a 2007 agreement and implement a Lower Basin commitment

to conserve 3 million acre-feet of water to address critical elevations in Lakes Powell and Mead through 2026.

This effort could add about 37 feet to Lake Mead by 2026.[26]

In August 2024 the Bureau of Reclamation determined the Lower Colorado River Basin will continue to be in a Tier 1 shortage for 2025.

In 2023 Lower Basin states and Mexico reduced their Colorado water use to 1983 levels.

Arizona reduced its use by one-third, to 1.89 million acre-feet, California by nearly 16% to 3.69 million acre-feet,

and Nevada by more than 36% to 190,000 acre-feet.

These reductions have stabilized Lake Mead, but Lake Powell is still in danger because of lower than average runoff and higher water use by Upper Basin states.[28]

One acre-foot equates to a yearly supply for three Arizona families.[5]

Sources:

[1]

USGS. (n. d.). Colorado River Basin focus area study.

https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/colorado-river-basin-focus-area-study?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

[2]

Geology.com. (n. d.). Utah lakes, rivers and water resources.

https://geology.com/lakes-rivers-water/utah.shtml

[3]

USGS. (n. d.). Rivers, streams and creeks.

https://www.usgs.gov/special-topic/water-science-school/science/rivers-streams-and-creeks?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

[4]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (n. d.). Colorado River management.

https://new.azwater.gov/crm/colorado-river-allocation

[5]

Central Arizona Project. (n. d.). Background and history.

https://www.cap-az.com/about/history-of-cap/

[6]

National Archives. (1928). Boulder Canyon Project Act, 1928.

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/boulder-canyon-project-act

[7]

U.S. Congress. (1948). Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, 1948.

https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/ucbsnact.pdf

For decades, the merits of building the dam and water sustainability versus the apparent destruction of geologic wonders and changes to the canyon's flora and fauna

have been debated by water managers and environmentalists.[14]

On May 22, 2023 Arizona, California and Nevada agreed to take less water from the Colorado.

In return the federal government will pay $1.2 billion to irrigation districts, cities and Tribes related to the cutbacks.

The agreement will end in 2026.

The reductions are about 13% of Lower Colorado Basin water use, about 3 million acre-feet of water over the next three-an-a-half years.[19]

Based on the Jan. 1, 2024 projected level of Lake Mead at 1065.27 feet above sea level, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior has declared a Tier 1 shortage for Colorado River operations in 2024.[23]

On May 24, 2023, Tucson mayor Regina Romero signed a groundbreaking water conservation agreement with the Bureau of Reclamation and CAP.

Under the agreement Tucson will be one of the first Arizona cities to leave a significant allocation of Colorado River water in Lake Mead

and voluntarily conserve up to 110,000 acre-feet of water over three years.[24]

In 2023 Arizona conserved about 950,000 acre-feet, including the required 592,000 Tier 2a reduction and

an additional voluntary contribution of 355,000 acre-feet to support the Colorado River system.[25]

In a study of 2023 Colorado River data, water journalist John Fleck concluded that in the Lower Basin, Nevada's use was the lowest since 1992,

Arizona's was the lowest since 1991, and California's use may have been the lowest since the late 1940s.[27]

In the Upper Basin there appears to be an upward water use trend with substantial annual variability, but the basin is using less than its

7.5 million acre feet allotted by the 1922 Colorado River Compact.[27]

On May 9, 2024, the Department of Interior signed a new Record of Decision (ROD) to supplement a 2007 agreement and implement a Lower Basin commitment

to conserve 3 million acre-feet of water to address critical elevations in Lakes Powell and Mead through 2026.

This effort could add about 37 feet to Lake Mead by 2026.[26]

In August 2024 the Bureau of Reclamation determined the Lower Colorado River Basin will continue to be in a Tier 1 shortage for 2025.

In 2023 Lower Basin states and Mexico reduced their Colorado water use to 1983 levels.

Arizona reduced its use by one-third, to 1.89 million acre-feet, California by nearly 16% to 3.69 million acre-feet,

and Nevada by more than 36% to 190,000 acre-feet.

These reductions have stabilized Lake Mead, but Lake Powell is still in danger because of lower than average runoff and higher water use by Upper Basin states.[28]

One acre-foot equates to a yearly supply for three Arizona families.[5]

Sources:

[1]

USGS. (n. d.). Colorado River Basin focus area study.

https://www.usgs.gov/mission-areas/water-resources/science/colorado-river-basin-focus-area-study?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

[2]

Geology.com. (n. d.). Utah lakes, rivers and water resources.

https://geology.com/lakes-rivers-water/utah.shtml

[3]

USGS. (n. d.). Rivers, streams and creeks.

https://www.usgs.gov/special-topic/water-science-school/science/rivers-streams-and-creeks?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

[4]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (n. d.). Colorado River management.

https://new.azwater.gov/crm/colorado-river-allocation

[5]

Central Arizona Project. (n. d.). Background and history.

https://www.cap-az.com/about/history-of-cap/

[6]

National Archives. (1928). Boulder Canyon Project Act, 1928.

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/boulder-canyon-project-act

[7]

U.S. Congress. (1948). Upper Colorado River Basin Compact, 1948.

https://www.usbr.gov/lc/region/pao/pdfiles/ucbsnact.pdf

[8]

Gelt, J. (Aug. 1997). Sharing Colorado River Water: History, public policy and the Colorado River Compact. Water Resources Research Center.

https://wrrc.arizona.edu/publications/arroyo-newsletter/sharing-colorado-river-water-history-public-policy-and-colorado-river

[9]

Petruzzello, M. (n. d.). Hoover Dam. Encyclopedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hoover-Dam

[10]

Bureau of Reclamation. (n. d.). Glen Canyon Unit. Interior region 7 - Upper Colorado Basin.

https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/gc/

[11]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (2022). Colorado River management.

https://new.azwater.gov/crm/colorado-river-allocation

[12]

Runyon, L. (Sep. 30, 2022). Federal officials set their sights on Lower Colorado River evaporation to speed up conservation. NPR for Northern Colorado.

https://www.kunc.org/environment/2022-09-30/federal-officials-set-their-sights-on-lower-colorado-river-evaporation-to-speed-up-conservation

[13]

U.S. Department of the Interior. (Oct. 12, 2022). Drought mitigation funding from Inflation Reduction Act.

https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/biden-harris-administration-announces-new-steps-drought-mitigation-funding-inflation#:~:text=The%20newly%20created%20Lower%20Colorado,for%20those%20who%20live%20in

[8]

Gelt, J. (Aug. 1997). Sharing Colorado River Water: History, public policy and the Colorado River Compact. Water Resources Research Center.

https://wrrc.arizona.edu/publications/arroyo-newsletter/sharing-colorado-river-water-history-public-policy-and-colorado-river

[9]

Petruzzello, M. (n. d.). Hoover Dam. Encyclopedia Britannica.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hoover-Dam

[10]

Bureau of Reclamation. (n. d.). Glen Canyon Unit. Interior region 7 - Upper Colorado Basin.

https://www.usbr.gov/uc/rm/crsp/gc/

[11]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (2022). Colorado River management.

https://new.azwater.gov/crm/colorado-river-allocation

[12]

Runyon, L. (Sep. 30, 2022). Federal officials set their sights on Lower Colorado River evaporation to speed up conservation. NPR for Northern Colorado.

https://www.kunc.org/environment/2022-09-30/federal-officials-set-their-sights-on-lower-colorado-river-evaporation-to-speed-up-conservation

[13]

U.S. Department of the Interior. (Oct. 12, 2022). Drought mitigation funding from Inflation Reduction Act.

https://www.doi.gov/pressreleases/biden-harris-administration-announces-new-steps-drought-mitigation-funding-inflation#:~:text=The%20newly%20created%20Lower%20Colorado,for%20those%20who%20live%20in

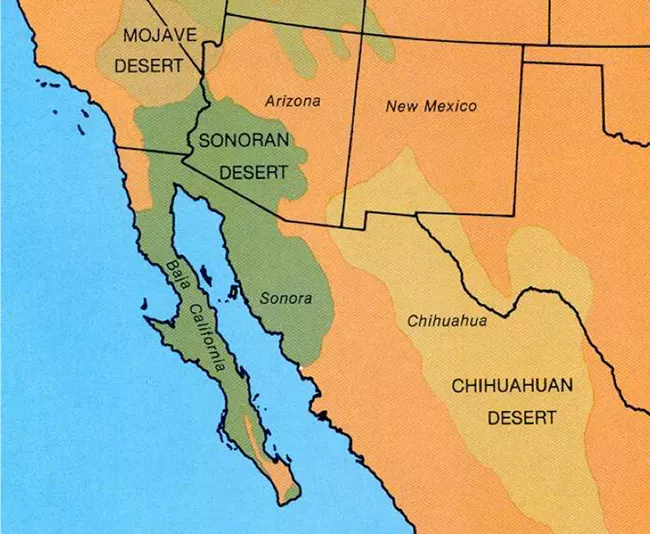

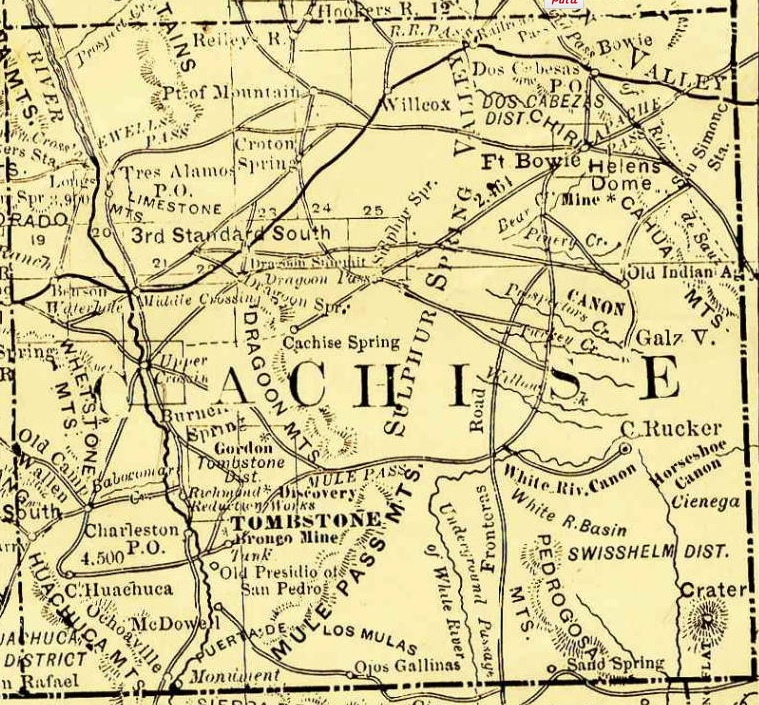

The desert seldom experiences earthquakes.

The last major earthquake, measured at 7.2 on the Richter scale and centered south of Douglas near Bavispe, Sonora, on the afternoon of May 3, 1887.

It created large dust clouds, massive rock falls, geysers and cracked walls.[2]

The oldest stratified rocks have been dated to about 1,200 million years ago.

They contain algae and small mushrooms that survived despite Precambrian tides.[2]

Paleozoic (570 to 240 mya) shales and limestones include

trilobites,an extinct fossil arthropod recognized by its distinctive three-lobed and three-segmented form

shark and fish teeth,

crinoids,any of a large class of invertebrates that are echinoderms and usually have a cup-shaped body with five or more feathery arms

coral,

bryzoans,a non-moving aquatic invertebrate of the phylum Bryozoa which comprises of the moss animals

conodonts,a fossil marine animal of the Cambrian to Triassic periods, having a long wormlike body, numerous small teeth and a pair of eyes, may be the earliest vertebrate

clams,

brachiopods,animal with a hard valve on its upper and lower surface

oysters and

cephalopods.an active predatory mollusk of the large class Cephalopoda such as an octopus or squid[2]

Mesozoic (150 to 90 mya) fossils include lizard tracks, turtles, horsetails and petrified wood, formed when the land rose and water drained.

Late Cretaceous rocks in the Santa Rita mountains include

sauropods,a very large plant-eating quadruped dinosaur with a long neck and tail, small head and massive limbs

horned and duckbilled dinosaurs and ancient mammals.[2]

Cenozoic rocks include fossil ancestors of modern horses,

titanotheresan extinct herbivorous hoofed mammal of the family Brontotheriidae of the Eocene and Oligocene epochs

and

oreodonts.an extinct, four-toed, ruminant, artiodactyl mammal of the Merycoidodontidae and Agriochoeridae families living in North America from the Eocene to the early Pliocene and resembling swine

Pleistocene fossils from the last two million years include camels, bison, modern horses,

mastodons,any of various extinct mammals of the elephant family existing from the Miocene through the Pleistocene distinguished by molar teeth with cone-shaped cusps

mammoths, giant ground sloths, wolves, lions, giant beavers and bears.[2]

The Pleistocene climate was characterized by glaciers and world-wide climate changes.

Arizona mountain glaciers existed above 9,000 feet (2,740 m), producing strong streams that transported rocks, soil and other debris from mountains and depositing

it in canyons.

The flowing water created

alluvial fansa fan-shaped mass of deposited material atthe mouth of a river or stream

that produced

bajadas.a broad alluvial slope from the base of a mountain range into a basin formed by joined alluvial fans

Below the bajadas are

pedimentsa broad, gently sloping expanse of buried rock debris extending outward from the foot of a mountain slope, especially in a desert

that prevented some valley alluvium and its water from flowing outward.[2]

Thousands of years of weathering have created rounded boulders and

hoodoosa column or pinnacle of weathered rock

along Gates Pass Road west of Tucson in Saguaro National Park, in the Santa Catalina mountains north of the city

along Mt. Lemmon Highway, in Texas Canyon along I-10 east of Benson and on Camelback Mountain in Phoenix.[2]

The desert seldom experiences earthquakes.

The last major earthquake, measured at 7.2 on the Richter scale and centered south of Douglas near Bavispe, Sonora, on the afternoon of May 3, 1887.

It created large dust clouds, massive rock falls, geysers and cracked walls.[2]

The oldest stratified rocks have been dated to about 1,200 million years ago.

They contain algae and small mushrooms that survived despite Precambrian tides.[2]

Paleozoic (570 to 240 mya) shales and limestones include

trilobites,an extinct fossil arthropod recognized by its distinctive three-lobed and three-segmented form

shark and fish teeth,

crinoids,any of a large class of invertebrates that are echinoderms and usually have a cup-shaped body with five or more feathery arms

coral,

bryzoans,a non-moving aquatic invertebrate of the phylum Bryozoa which comprises of the moss animals

conodonts,a fossil marine animal of the Cambrian to Triassic periods, having a long wormlike body, numerous small teeth and a pair of eyes, may be the earliest vertebrate

clams,

brachiopods,animal with a hard valve on its upper and lower surface

oysters and

cephalopods.an active predatory mollusk of the large class Cephalopoda such as an octopus or squid[2]

Mesozoic (150 to 90 mya) fossils include lizard tracks, turtles, horsetails and petrified wood, formed when the land rose and water drained.

Late Cretaceous rocks in the Santa Rita mountains include

sauropods,a very large plant-eating quadruped dinosaur with a long neck and tail, small head and massive limbs

horned and duckbilled dinosaurs and ancient mammals.[2]

Cenozoic rocks include fossil ancestors of modern horses,

titanotheresan extinct herbivorous hoofed mammal of the family Brontotheriidae of the Eocene and Oligocene epochs

and

oreodonts.an extinct, four-toed, ruminant, artiodactyl mammal of the Merycoidodontidae and Agriochoeridae families living in North America from the Eocene to the early Pliocene and resembling swine

Pleistocene fossils from the last two million years include camels, bison, modern horses,

mastodons,any of various extinct mammals of the elephant family existing from the Miocene through the Pleistocene distinguished by molar teeth with cone-shaped cusps

mammoths, giant ground sloths, wolves, lions, giant beavers and bears.[2]

The Pleistocene climate was characterized by glaciers and world-wide climate changes.

Arizona mountain glaciers existed above 9,000 feet (2,740 m), producing strong streams that transported rocks, soil and other debris from mountains and depositing

it in canyons.

The flowing water created

alluvial fansa fan-shaped mass of deposited material atthe mouth of a river or stream

that produced

bajadas.a broad alluvial slope from the base of a mountain range into a basin formed by joined alluvial fans

Below the bajadas are

pedimentsa broad, gently sloping expanse of buried rock debris extending outward from the foot of a mountain slope, especially in a desert

that prevented some valley alluvium and its water from flowing outward.[2]

Thousands of years of weathering have created rounded boulders and

hoodoosa column or pinnacle of weathered rock

along Gates Pass Road west of Tucson in Saguaro National Park, in the Santa Catalina mountains north of the city

along Mt. Lemmon Highway, in Texas Canyon along I-10 east of Benson and on Camelback Mountain in Phoenix.[2]

The five Tribes for which the U.S. filed water rights claims in the previous proceedings moved to intervene and made additional water claims.

The Supreme Court denied those motions.[4]

In 1979 a Supplemental Decree

established "present perfected rights to the use of the mainstream water in each State and their priority dates,"

describing Tribal water rights and noting those rights "shall continue to be subject to appropriate adjustment by agreement or decree of this Court."[4]

The Court referred the matters to a new special master who determined that the Secretary of the Interior's orders

issued between 1969 and 1978 had determined the Tribes' reservation boundaries for purposes of the

1964 Decree.

Those boundary lands determinations increased reservation land areas and entitled Tribes to additional water.[4]

The special master also decided that there were additional lands in the 1964 boundaries entitled to water.

In a 1983 ruling the Court rejected this recommendation, refusing to reopen the

1964 Decree

to award the Tribes additional waters.

The Court held that the Secretary's findings were not final determinations because the affected states had not had an opportunity to seek judicial review.

The California water agencies challenged the Secretary's findings in federal district court.[4]

After this ruling the states and agencies petitioned the Court to reopen its

1964 Decree,

seeking a ruling on whether the Quechan, Fort Mojave and Colorado River Indian Reservations were entitled to additional boundary lands and

whether the Tribes were entitled to additional water rights.[4]

The Court appointed two new special masters who issued orders resulting in a report recommending

the Court approve proposed settlements regarding the Fort Mojave and Colorado River Indian Reservations.

The special masters' report did not favor additional water for the Quechan Tribe on the grounds that a judgment of the Court of Claims had divested

the Tribe of any claim to the boundary lands and corresponding water rights.[4]

In a 1989 ruling the Supreme Court approved the Fort Mojave and Colorado River Reservations settlement agreements.

In 2000 the Court rejected the special master's recommendation that the Quechan Tribe was precluded from pursuing a claim.[4]

After the 2000 ruling the parties made several attempts to settle the claims of the Quechan Tribe, resulting in agreements with

Arizona, California and Colorado water districts that were approved by the Supreme Court in 2005.

The settlements provided the Tribe with over 26,000 acre-feet of water per year.[4]

Even though Tribes in the Colorado River basin are among the most senior water rights holders, the amount and access for the

Havasupai, Hopi, Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Navajo Nation, Pasqua Yaqui, San Juan Southern Paiute,

Tonto Apache and Yavapai-Apache Nation Tribes is unresolved.[5]

The five Tribes for which the U.S. filed water rights claims in the previous proceedings moved to intervene and made additional water claims.

The Supreme Court denied those motions.[4]

In 1979 a Supplemental Decree

established "present perfected rights to the use of the mainstream water in each State and their priority dates,"

describing Tribal water rights and noting those rights "shall continue to be subject to appropriate adjustment by agreement or decree of this Court."[4]

The Court referred the matters to a new special master who determined that the Secretary of the Interior's orders

issued between 1969 and 1978 had determined the Tribes' reservation boundaries for purposes of the

1964 Decree.

Those boundary lands determinations increased reservation land areas and entitled Tribes to additional water.[4]

The special master also decided that there were additional lands in the 1964 boundaries entitled to water.

In a 1983 ruling the Court rejected this recommendation, refusing to reopen the

1964 Decree

to award the Tribes additional waters.

The Court held that the Secretary's findings were not final determinations because the affected states had not had an opportunity to seek judicial review.

The California water agencies challenged the Secretary's findings in federal district court.[4]

After this ruling the states and agencies petitioned the Court to reopen its

1964 Decree,

seeking a ruling on whether the Quechan, Fort Mojave and Colorado River Indian Reservations were entitled to additional boundary lands and

whether the Tribes were entitled to additional water rights.[4]

The Court appointed two new special masters who issued orders resulting in a report recommending

the Court approve proposed settlements regarding the Fort Mojave and Colorado River Indian Reservations.

The special masters' report did not favor additional water for the Quechan Tribe on the grounds that a judgment of the Court of Claims had divested

the Tribe of any claim to the boundary lands and corresponding water rights.[4]

In a 1989 ruling the Supreme Court approved the Fort Mojave and Colorado River Reservations settlement agreements.

In 2000 the Court rejected the special master's recommendation that the Quechan Tribe was precluded from pursuing a claim.[4]

After the 2000 ruling the parties made several attempts to settle the claims of the Quechan Tribe, resulting in agreements with

Arizona, California and Colorado water districts that were approved by the Supreme Court in 2005.

The settlements provided the Tribe with over 26,000 acre-feet of water per year.[4]

Even though Tribes in the Colorado River basin are among the most senior water rights holders, the amount and access for the

Havasupai, Hopi, Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians, Navajo Nation, Pasqua Yaqui, San Juan Southern Paiute,

Tonto Apache and Yavapai-Apache Nation Tribes is unresolved.[5]

[1]

World Atlas. (2022). The ten longest rivers in Arizona.

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-10-longest-rivers-in-arizona.html

[2]

American Rivers. (2021). Gila River: The origin of wilderness.

https://www.americanrivers.org/river/gila-river/

[3]

Sonoran Institute. (2023). Resources: Arizona reports.

https://sonoraninstitute.org/resources/arizona-reports/

[4]

Nature Conservancy. (2023). Arizona rivers & water.

https://azconservation.org/project/water/

[5]

Gerbis, N. (Feb. 26, 2021). Untold Arizona: Tracing the ancient origins of Arizona rivers. KJZZ.

https://kjzz.org/content/852596/untold-arizona-tracing-ancient-origins-arizona-rivers

[6]

Center for American Progress. (Feb. 2018). Arizona's disappearing rivers.

https://disappearingwest.org/rivers/factsheets/DisappearingRivers-AZ-factsheet.pdf

[7]

Hube, E-M. (Apr. 24, 2023). Once-common San Pedro River beavers making tiny comeback. Arizona Daily Star.

https://tucson.com/news/local/once-common-san-pedro-river-beavers-making-tiny-comeback/article_a30c94da-df12-11ed-8ae4-734100e4eb96.html

[8]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (May 4, 2023). Restoration project supported by ADWR's Water Protection Fund deemed a 'great success.'

https://new.azwater.gov/news/articles/2023-04-05-0

[1]

World Atlas. (2022). The ten longest rivers in Arizona.

https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-10-longest-rivers-in-arizona.html

[2]

American Rivers. (2021). Gila River: The origin of wilderness.

https://www.americanrivers.org/river/gila-river/

[3]

Sonoran Institute. (2023). Resources: Arizona reports.

https://sonoraninstitute.org/resources/arizona-reports/

[4]

Nature Conservancy. (2023). Arizona rivers & water.

https://azconservation.org/project/water/

[5]

Gerbis, N. (Feb. 26, 2021). Untold Arizona: Tracing the ancient origins of Arizona rivers. KJZZ.

https://kjzz.org/content/852596/untold-arizona-tracing-ancient-origins-arizona-rivers

[6]

Center for American Progress. (Feb. 2018). Arizona's disappearing rivers.

https://disappearingwest.org/rivers/factsheets/DisappearingRivers-AZ-factsheet.pdf

[7]

Hube, E-M. (Apr. 24, 2023). Once-common San Pedro River beavers making tiny comeback. Arizona Daily Star.

https://tucson.com/news/local/once-common-san-pedro-river-beavers-making-tiny-comeback/article_a30c94da-df12-11ed-8ae4-734100e4eb96.html

[8]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (May 4, 2023). Restoration project supported by ADWR's Water Protection Fund deemed a 'great success.'

https://new.azwater.gov/news/articles/2023-04-05-0

In June 1920 the ECLA and SRVWUA reached an agreement that allowed ECLA to expand the canal system in the southern and western parts of the valley,

but ECLA later gave up its claim, renamed itself the Roosevelt Water Conservation District (RWCD).[1]

The Verde River Irrigation and Power District (VRIPD) wanted to divert water that was being used by the SRP, but like ECLA, lacked funding and political support to

build the proposed Verde Dam.[1]

In 1930 groundwater had become scarce, with reservoir storage at close to 100,000 acre-feet.

SRP turned to groundwater and installed 45 high-capacity pumping plants in less than a year.[1]

SRVWUA then had a bonded debt of $11 million for three Salt River dams, and owed the federal government $4.8 million

for the balance of the Roosevelt Dam costs.

SRVWUA requested another $3.6 million from the federal government, agreeing to pay back all of its federal debts over the next 20 years.[1]

During and after the Great Depression, SRVWUA managed to maintain its credit rating and managed to collect payments from water users.[1]

In 1933 the Public Works Administration (PWA) provided the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which established an office in Phoenix, $19 million

to finance the Verde project.

But reports indicated that the project was ill-advised.[1]

In 1936 the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors approved SRVWUA's request to form the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District (SRPAIPD),

separating the Salt River water and power management functions.[1]

The Bartlett Dam was started in 1937 and completed in 1939, creating a 2,185 acre reservoir that stored 180,000 acre-feet of water.

This dam was financed with federal funds and built by the Bureau of Reclamation, symbolizing the relationships between SRP and the federal government.[1]

In June 1920 the ECLA and SRVWUA reached an agreement that allowed ECLA to expand the canal system in the southern and western parts of the valley,

but ECLA later gave up its claim, renamed itself the Roosevelt Water Conservation District (RWCD).[1]

The Verde River Irrigation and Power District (VRIPD) wanted to divert water that was being used by the SRP, but like ECLA, lacked funding and political support to

build the proposed Verde Dam.[1]

In 1930 groundwater had become scarce, with reservoir storage at close to 100,000 acre-feet.

SRP turned to groundwater and installed 45 high-capacity pumping plants in less than a year.[1]

SRVWUA then had a bonded debt of $11 million for three Salt River dams, and owed the federal government $4.8 million

for the balance of the Roosevelt Dam costs.

SRVWUA requested another $3.6 million from the federal government, agreeing to pay back all of its federal debts over the next 20 years.[1]

During and after the Great Depression, SRVWUA managed to maintain its credit rating and managed to collect payments from water users.[1]

In 1933 the Public Works Administration (PWA) provided the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, which established an office in Phoenix, $19 million

to finance the Verde project.

But reports indicated that the project was ill-advised.[1]

In 1936 the Maricopa County Board of Supervisors approved SRVWUA's request to form the Salt River Project Agricultural Improvement and Power District (SRPAIPD),

separating the Salt River water and power management functions.[1]

The Bartlett Dam was started in 1937 and completed in 1939, creating a 2,185 acre reservoir that stored 180,000 acre-feet of water.

This dam was financed with federal funds and built by the Bureau of Reclamation, symbolizing the relationships between SRP and the federal government.[1]

Southwestern North America has been suffering a

megadroughta drought lasting for more than two decades

since 2000.

The current drought has exceeded the severity of a late-1500s megadrought identified as the driest in 1,200 years.

Several wet years are required to alleviate the drought it would take multiple wet years to remediate the drought.[16]

Researchers analyzing tree rings from southern Montana to northern Mexico and between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains

identified past moisture levels and found that severe droughts were marked by a lack of soil moisture.

They also discovered that megadroughts occurred repeatedly in that region between 800 and 1600, confirming that droughts were a natural occurence.[16]

But climate change has made droughts far worse than those of the past.

Human-caused climate change responsible for about 42% of the soil moisture deficit since 2000.

Warmer temperatures increase evaporation, drying soil and vegetation.[16]

The 2004 Arizona Drought Preparedness Plan created the Drought Interagency Coordinating Group.

The group includes representatives from state, federal and non-governmental organizations.

They identify drought mitigation and adaptation options, advise the governor about drought conditions, request drought declarations,

review and approve the

Arizona Drought Preparedness Plans & Annual Reports

and make recommendations on drought monitoring and response implementation.[19]

In 2018 and early 2019 Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) and Central Arizona Project (CAP) led nearly 40 stakeholders through months of public and small group meetings with the goal of negotiating reductions from

Colorado River allocations.[4]

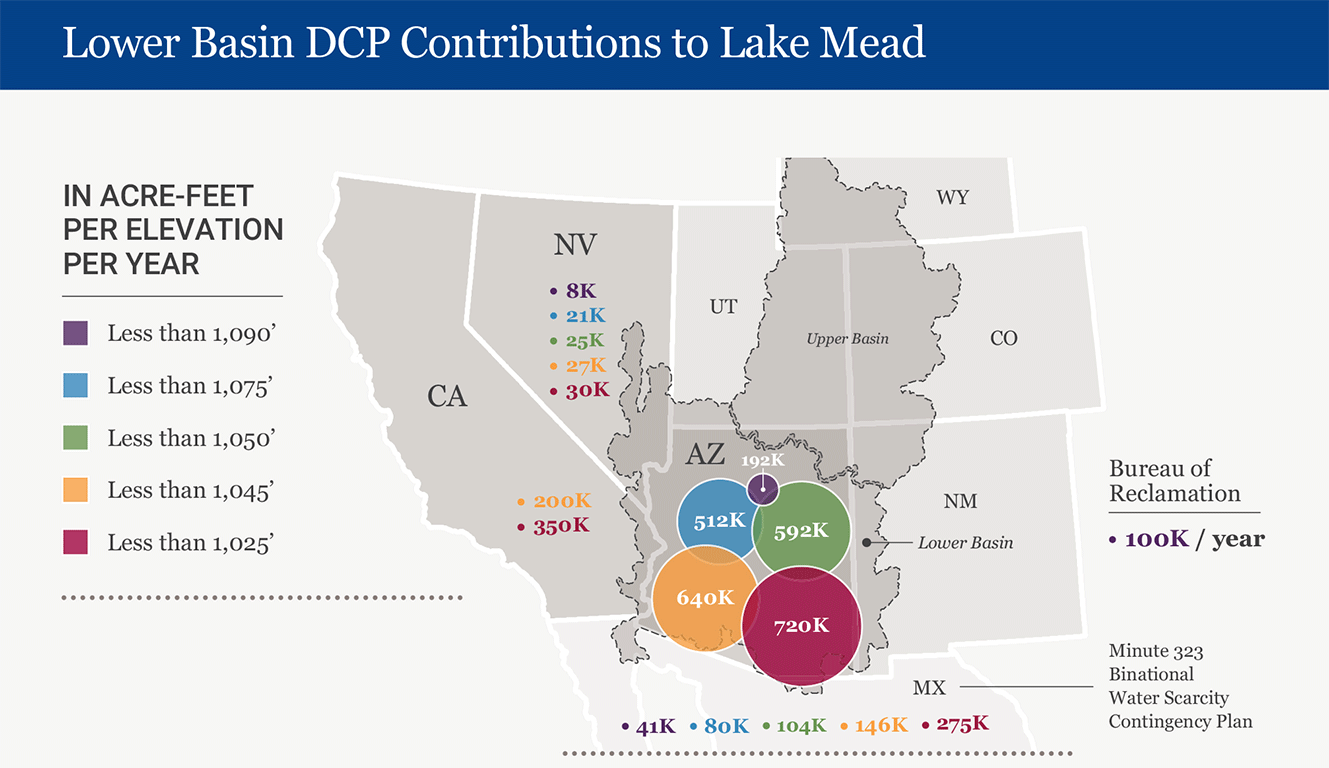

In 2020 and 2021 the river operated at Tier Zero status, requiring Arizona to forego 192,000 acre-feet of the state's 2.8-million acre-foot annual

entitlement to Lake Mead.

The reduction was entirely from the CAP system.[3]

In August 2021 the U.S. Secretary of the Interior declared the first-ever Tier 1 shortage for Colorado River operations

requiring Arizona to further reduce uses to a total of 512,000 acre-feet from the CAP.[3]

Arizona has how many miles of rivers?

Tier 1 reductions constitute about 30% of CAP's normal supply, about 18% of Arizona's Colorado River supply and less than 8% of Arizona's total water use.[3]

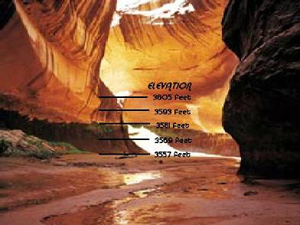

On February 14, 2023 Lake Powell, about 22% full, dropped to a record low of 3,522 feet above sea level, the lowest it has been since it was filled in the 1960s.

The level is expected to continue declining until May, when mountain snowmelt will join streams flowing into the lake.[10]

The bottom of Lake Powell is now covered by a layer of Colorado River sediment, estimated to be at least 100 feet thick.

The layer is called the Dominy formation, named after Floyd Dominy, who led Glen Canyon Dam construction as the head of the Bureau of Reclamation.

Dominy claimed that it would take thousands of years for the reservoir to fill with sediment.[11]

Southwestern North America has been suffering a

megadroughta drought lasting for more than two decades

since 2000.

The current drought has exceeded the severity of a late-1500s megadrought identified as the driest in 1,200 years.

Several wet years are required to alleviate the drought it would take multiple wet years to remediate the drought.[16]

Researchers analyzing tree rings from southern Montana to northern Mexico and between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains

identified past moisture levels and found that severe droughts were marked by a lack of soil moisture.

They also discovered that megadroughts occurred repeatedly in that region between 800 and 1600, confirming that droughts were a natural occurence.[16]

But climate change has made droughts far worse than those of the past.

Human-caused climate change responsible for about 42% of the soil moisture deficit since 2000.

Warmer temperatures increase evaporation, drying soil and vegetation.[16]

The 2004 Arizona Drought Preparedness Plan created the Drought Interagency Coordinating Group.

The group includes representatives from state, federal and non-governmental organizations.

They identify drought mitigation and adaptation options, advise the governor about drought conditions, request drought declarations,

review and approve the

Arizona Drought Preparedness Plans & Annual Reports

and make recommendations on drought monitoring and response implementation.[19]

In 2018 and early 2019 Arizona Department of Water Resources (ADWR) and Central Arizona Project (CAP) led nearly 40 stakeholders through months of public and small group meetings with the goal of negotiating reductions from

Colorado River allocations.[4]

In 2020 and 2021 the river operated at Tier Zero status, requiring Arizona to forego 192,000 acre-feet of the state's 2.8-million acre-foot annual

entitlement to Lake Mead.

The reduction was entirely from the CAP system.[3]

In August 2021 the U.S. Secretary of the Interior declared the first-ever Tier 1 shortage for Colorado River operations

requiring Arizona to further reduce uses to a total of 512,000 acre-feet from the CAP.[3]

Arizona has how many miles of rivers?

Tier 1 reductions constitute about 30% of CAP's normal supply, about 18% of Arizona's Colorado River supply and less than 8% of Arizona's total water use.[3]

On February 14, 2023 Lake Powell, about 22% full, dropped to a record low of 3,522 feet above sea level, the lowest it has been since it was filled in the 1960s.

The level is expected to continue declining until May, when mountain snowmelt will join streams flowing into the lake.[10]

The bottom of Lake Powell is now covered by a layer of Colorado River sediment, estimated to be at least 100 feet thick.

The layer is called the Dominy formation, named after Floyd Dominy, who led Glen Canyon Dam construction as the head of the Bureau of Reclamation.

Dominy claimed that it would take thousands of years for the reservoir to fill with sediment.[11]

When exposed this broken sediment, which has captured tons of water, releases

methanea powerful greenhouse gas and the simplest hydrocarbon, consisting of one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms

from rotting trees.

During flash floods, the muddy layer flows downstream with its captured

biomatter,mass of living matter within a given area

damaging ecosystems, displacing and killing both flora and fauna, including otters,

native fish, willows and cottonwoods.[11]

In 2022, Cathedral in the Desert, a feature that has not been visible since the 1960s, could be accessed by boat.

By 2023 visitors had to secure boats downstream and walk 15 minutes along a small creek through which even small boats cannot pass.

As the reservoir continues to decline, the journey by foot will increase.[11]

Some environmentalists view Lake Powell's decreasing water supply as an opportunity for the area to return to its natural state, before the Glen Canyon Dam was built.

Because the water level has declined, however, hydropower turbines are now using warm surface water, making conditions more hospitable for non-native fish which are

competing with native species.[11]

The seven Colorado River Basin States, along with water entitlement holders in the Lower Basin, developed

Upper Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plan and a

Lower Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plan.[1]

The Upper and Lower Basins of the Colorado were each allocated 7.5 million acre-feet of water.

The Upper Basin plan is designed to:

When exposed this broken sediment, which has captured tons of water, releases

methanea powerful greenhouse gas and the simplest hydrocarbon, consisting of one carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms

from rotting trees.

During flash floods, the muddy layer flows downstream with its captured

biomatter,mass of living matter within a given area

damaging ecosystems, displacing and killing both flora and fauna, including otters,

native fish, willows and cottonwoods.[11]

In 2022, Cathedral in the Desert, a feature that has not been visible since the 1960s, could be accessed by boat.

By 2023 visitors had to secure boats downstream and walk 15 minutes along a small creek through which even small boats cannot pass.

As the reservoir continues to decline, the journey by foot will increase.[11]

Some environmentalists view Lake Powell's decreasing water supply as an opportunity for the area to return to its natural state, before the Glen Canyon Dam was built.

Because the water level has declined, however, hydropower turbines are now using warm surface water, making conditions more hospitable for non-native fish which are

competing with native species.[11]

The seven Colorado River Basin States, along with water entitlement holders in the Lower Basin, developed

Upper Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plan and a

Lower Colorado River Basin Drought Contingency Plan.[1]

The Upper and Lower Basins of the Colorado were each allocated 7.5 million acre-feet of water.

The Upper Basin plan is designed to:

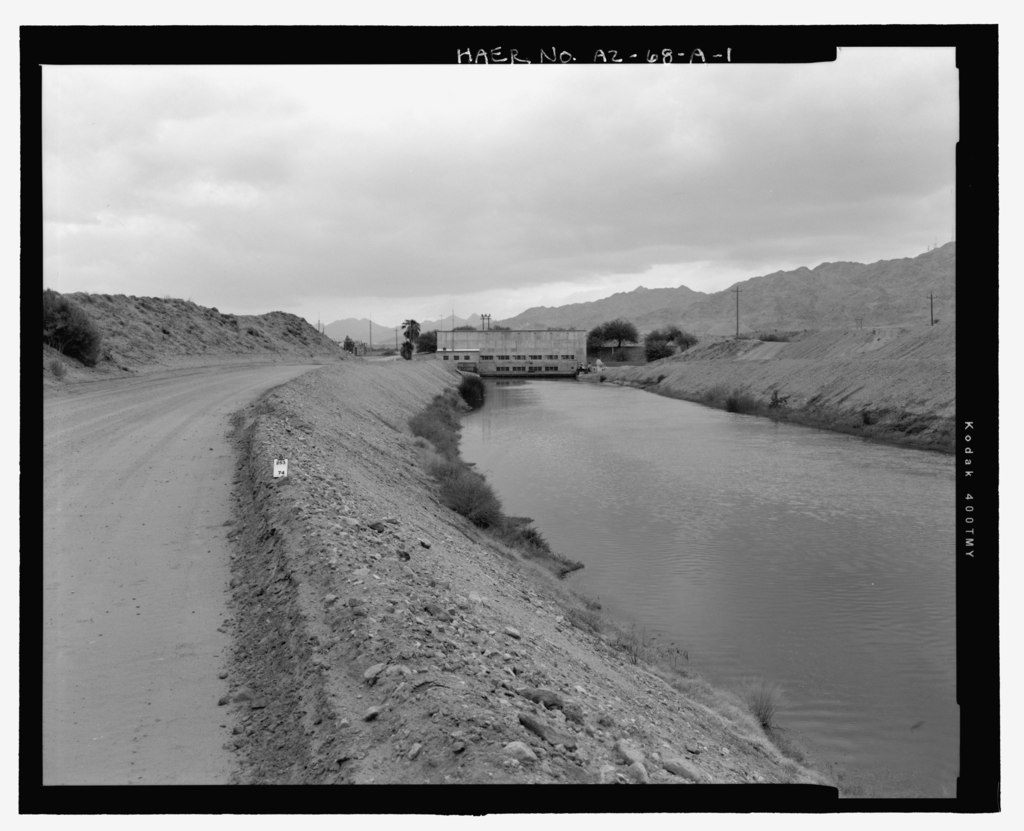

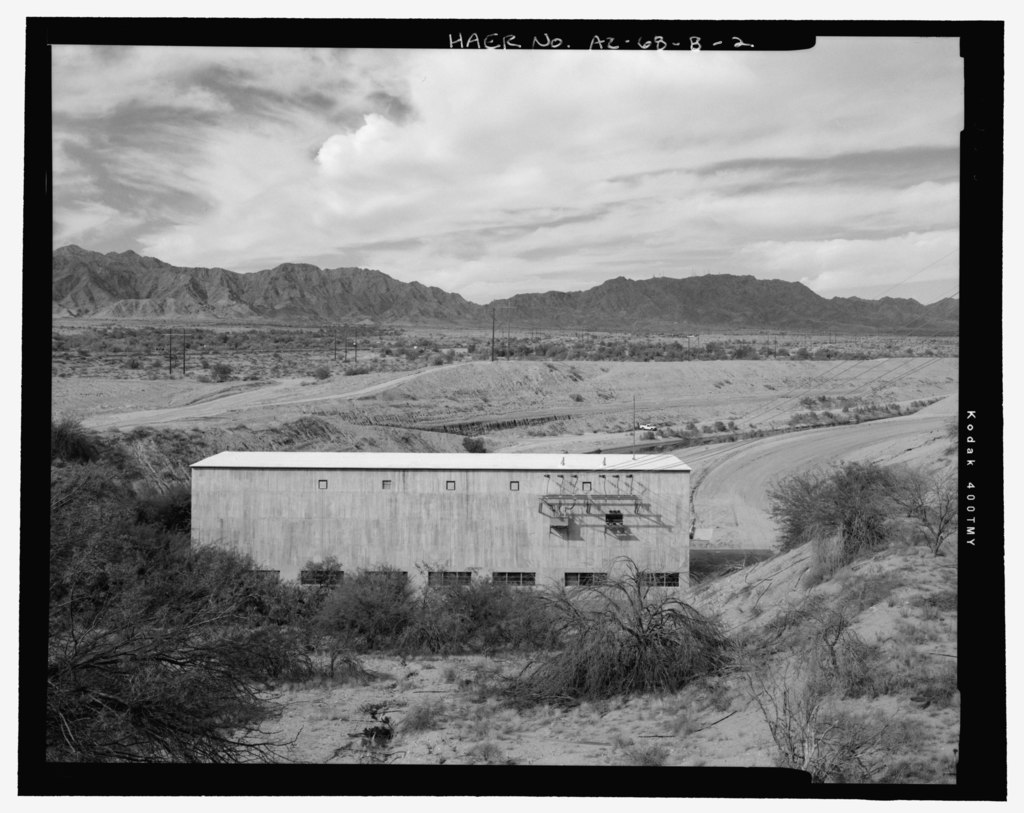

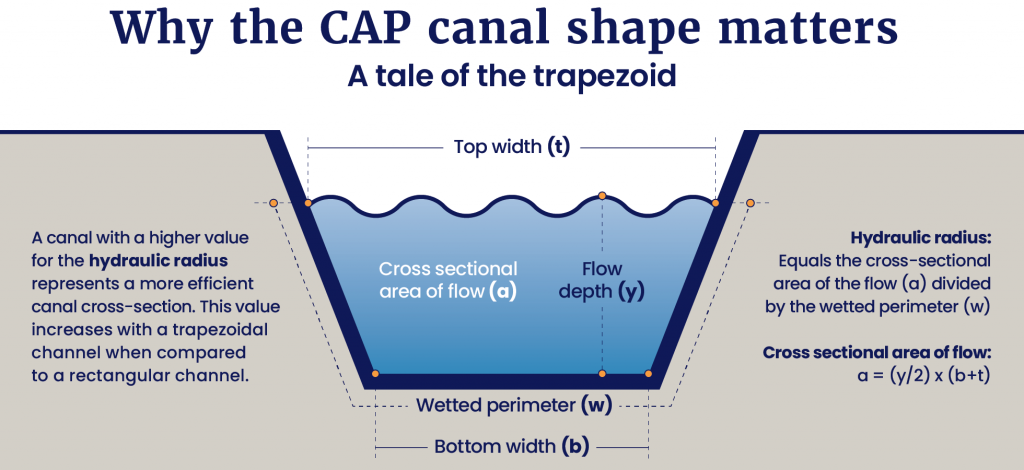

CAP is the state's single largest power user, utilizing 2.5 million

megawatt1,000 kilowatts, the power used by the average microwave oven

hours per year, about the same amount of energy used by 250,000 homes.

The system pumps water uphill from the Mark Wilmer Pumping Plant.

Six 66,000 horsepower pumps force water up 800 vertical feet into the seven-mile long Buckskin Mountain Tunnel.

The water then flows into and continues through the canal to Tucson.[1]

The canal is 336 miles long.

The system has 39 check structures acting as a metering devices, controlling the flow of water into and out of parts of the canal.

Each check structure contains two independently operating gates that can move in 1/100 foot increments.

The maximum structure capacity is 3,000 cubic feet per second.[13]

Fourteen pumping plants lift the water more than 2,900 feet before it starts its journey to Tucson,

which takes between five and seven days.

On its way, the water passes through the hydroelectric pump and generating plant at

New Waddell Dam,

CAP is the state's single largest power user, utilizing 2.5 million

megawatt1,000 kilowatts, the power used by the average microwave oven

hours per year, about the same amount of energy used by 250,000 homes.

The system pumps water uphill from the Mark Wilmer Pumping Plant.

Six 66,000 horsepower pumps force water up 800 vertical feet into the seven-mile long Buckskin Mountain Tunnel.

The water then flows into and continues through the canal to Tucson.[1]

The canal is 336 miles long.

The system has 39 check structures acting as a metering devices, controlling the flow of water into and out of parts of the canal.

Each check structure contains two independently operating gates that can move in 1/100 foot increments.

The maximum structure capacity is 3,000 cubic feet per second.[13]

Fourteen pumping plants lift the water more than 2,900 feet before it starts its journey to Tucson,

which takes between five and seven days.

On its way, the water passes through the hydroelectric pump and generating plant at

New Waddell Dam,

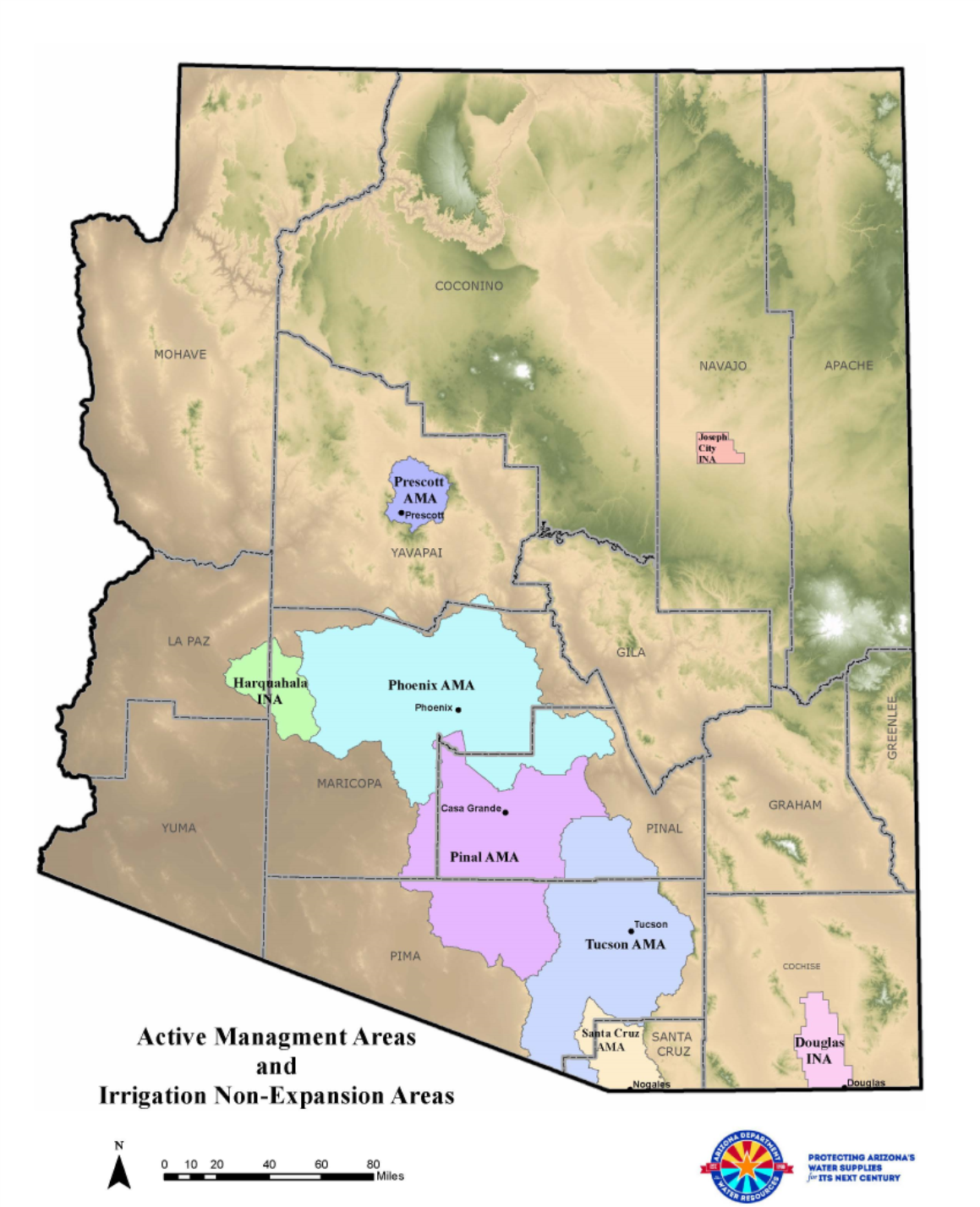

Arizona was depleting underground aquifers.

A 1976 state Supreme Court decision on groundwater pumping threatened to decimate Tucson's mining industry.

Governor Bruce Babbitt and the state legislature managed to work together to pass this act that assured that Arizona had water, when other states,

especially California, were dealing with shortages.[3]

ADWR measures groundwater levels in Arizona basins on a rotating basis.

AMAs and

irrigation non-expansion areas (INA)area designated to protect existing agriculture where groundwater is the main water source

have priority.

These efforts, called basin sweeps, collect well water, groundwater and water quality data used in water management and planning.[16]

The GMA created the Joseph City and Douglas INAs.[28]

The Douglas INA became and AMA in 2022.

The Harquahala INA was created in 1981 and the Hualapai Valley INA in 2022,

They are administered by ADWR.[21]

On June 28, 2021, ADWR updated groundwater conditions in the Pinal AMA.

The results demonstrated that between 2016 and 2115 groundwater demand would exceed supply by 8 million acre-feet.[15]

In January 2023, ADWR published the

Hassayampa Groundwater Model,

which projects water use west of the White Tank mountains and northwest of Phoenix.

The analysis determined that demand would exceed supply by 4.4 million acre-feet of groundwater over a 100-year period for the area,

meaning that future subdivisions relying on groundwater would not be approved.[15]

Outside AMAs there are few groundwater use restrictions, resulting in limited legal protections for local communities

that want to prevent new and existing groundwater user from overpumping, reducing groundwater reserves and creating potential shortages.[2]

Counties and municipalities outside AMAs can sign up for additional protections.

Cochise and Yuma Counties and Clarkdale and Patagonia require new development to prove it can meet the 100 year water requirements of AMAs.[2]

The San Pedro and the Verde Rivers flow because of groundwater,

but Arizona water law does not adequately protect the relationship between groundwater and surface water.[2]

When Colorado River supply exceeds demand, municipalities can store the excess water underground, earning long-term storage credits.

The state tracks those credits, and cities can then return that water into the ground when needed.

Reclaimed water, however, earns fewer storage credits.[2]

In 1993 the Arizona State legislature created a groundwater replenishment authority to be operated by the Central Arizona Water Conservation District (CAWCD)

throughout its three-county service area.

This replenishment authority of CAWCD is called the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District (CAGRD).[4]

Arizona was depleting underground aquifers.

A 1976 state Supreme Court decision on groundwater pumping threatened to decimate Tucson's mining industry.

Governor Bruce Babbitt and the state legislature managed to work together to pass this act that assured that Arizona had water, when other states,

especially California, were dealing with shortages.[3]

ADWR measures groundwater levels in Arizona basins on a rotating basis.

AMAs and

irrigation non-expansion areas (INA)area designated to protect existing agriculture where groundwater is the main water source

have priority.

These efforts, called basin sweeps, collect well water, groundwater and water quality data used in water management and planning.[16]

The GMA created the Joseph City and Douglas INAs.[28]

The Douglas INA became and AMA in 2022.

The Harquahala INA was created in 1981 and the Hualapai Valley INA in 2022,

They are administered by ADWR.[21]

On June 28, 2021, ADWR updated groundwater conditions in the Pinal AMA.

The results demonstrated that between 2016 and 2115 groundwater demand would exceed supply by 8 million acre-feet.[15]

In January 2023, ADWR published the

Hassayampa Groundwater Model,

which projects water use west of the White Tank mountains and northwest of Phoenix.

The analysis determined that demand would exceed supply by 4.4 million acre-feet of groundwater over a 100-year period for the area,

meaning that future subdivisions relying on groundwater would not be approved.[15]

Outside AMAs there are few groundwater use restrictions, resulting in limited legal protections for local communities

that want to prevent new and existing groundwater user from overpumping, reducing groundwater reserves and creating potential shortages.[2]

Counties and municipalities outside AMAs can sign up for additional protections.

Cochise and Yuma Counties and Clarkdale and Patagonia require new development to prove it can meet the 100 year water requirements of AMAs.[2]

The San Pedro and the Verde Rivers flow because of groundwater,

but Arizona water law does not adequately protect the relationship between groundwater and surface water.[2]

When Colorado River supply exceeds demand, municipalities can store the excess water underground, earning long-term storage credits.

The state tracks those credits, and cities can then return that water into the ground when needed.

Reclaimed water, however, earns fewer storage credits.[2]

In 1993 the Arizona State legislature created a groundwater replenishment authority to be operated by the Central Arizona Water Conservation District (CAWCD)

throughout its three-county service area.

This replenishment authority of CAWCD is called the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District (CAGRD).[4]

The USGS monitors groundwater storage and land elevation changes caused by groundwater removal in Tucson Basin and Avra Valley,

the two most populated

alluvial plainsa largely flat landform created by the deposition of sediment over a long period of time by one or more rivers coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms

within the Tucson AMA.

It is one of five areas established by the

1980 Groundwater Management Act

and governed by the Arizona Department of Water Resources.[6]

The USGS used radar to track the changes and found the maximum subsidence of about 2 inches occurred between May 2003 to July 2006, and then declined to

0.9 inches between April 2011 and November 2014.[6]

Between May 2003 and March 2016, maximum subsidence was as high as 5.3 inches in the Tucson metropolitan area,

south of Irvington Road between south 12th Avenue and south Park Avenue.

Subsidence was as high as 4 inches in central Tucson south of Broadway between Country Club Road and Craycroft Road.[6]

The radar data indicated that there was no significant land surface deformation from 2003 to 2016 in Avra Valley.[6]

There are areas of Arizona outside of AMAs, where groundwater sources are declining.

Willcox Basin relies on only rainfall alone for replenishment and is vulnerable during drought.[12]

When large water-using operations, like the Riverview Dairy, moved in to the area residents noticed that their water disappearing

because the dairy was pumping out a lot of groundwater from deep wells, causing residents' wells to dry up.[12]

In 2006 Congress passed

U.S. Public Law 109-448 the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Act,

a federally funded program co-hosted by the

U.S.G.S. Arizona Water Science Center and the University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center (WRRC).[23]

The act applies to Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, where four transboundary aquifers have been designated for priority assessment.

The Hueco Bolson and Mesilla Basin aquifers are in the greater El Paso and Ciudad Juárez region.

The Santa Cruz and San Pedro aquifers cross the Arizona-Sonora border.[23]

The USGS monitors groundwater storage and land elevation changes caused by groundwater removal in Tucson Basin and Avra Valley,

the two most populated

alluvial plainsa largely flat landform created by the deposition of sediment over a long period of time by one or more rivers coming from highland regions, from which alluvial soil forms

within the Tucson AMA.

It is one of five areas established by the

1980 Groundwater Management Act

and governed by the Arizona Department of Water Resources.[6]

The USGS used radar to track the changes and found the maximum subsidence of about 2 inches occurred between May 2003 to July 2006, and then declined to

0.9 inches between April 2011 and November 2014.[6]

Between May 2003 and March 2016, maximum subsidence was as high as 5.3 inches in the Tucson metropolitan area,

south of Irvington Road between south 12th Avenue and south Park Avenue.

Subsidence was as high as 4 inches in central Tucson south of Broadway between Country Club Road and Craycroft Road.[6]

The radar data indicated that there was no significant land surface deformation from 2003 to 2016 in Avra Valley.[6]

There are areas of Arizona outside of AMAs, where groundwater sources are declining.

Willcox Basin relies on only rainfall alone for replenishment and is vulnerable during drought.[12]

When large water-using operations, like the Riverview Dairy, moved in to the area residents noticed that their water disappearing

because the dairy was pumping out a lot of groundwater from deep wells, causing residents' wells to dry up.[12]

In 2006 Congress passed

U.S. Public Law 109-448 the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Act,

a federally funded program co-hosted by the

U.S.G.S. Arizona Water Science Center and the University of Arizona Water Resources Research Center (WRRC).[23]

The act applies to Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, where four transboundary aquifers have been designated for priority assessment.

The Hueco Bolson and Mesilla Basin aquifers are in the greater El Paso and Ciudad Juárez region.

The Santa Cruz and San Pedro aquifers cross the Arizona-Sonora border.[23]

Years of anti-regulation sentiment have led to a grassroots campaign for restrictions on new wells which could restrict future corporate farming operations.[12]

Within the 1980 Groundwater Management Act

is a provision allowing rural communities to propose a ballot question about whether to establish an AMA.

If the ballot question wins a majority vote, the state then appoints a committee to supervise groundwater in the basin.

The committee can impose restrictions on new irrigation activity, limiting land area using groundwater.[12],[27],

A group called the Arizona Water Defenders wants to create a new AMA to regulate groundwater in the conservative Willcox and Douglas Basins.

They had no difficulty obtaining the required 250 signatures from Cochise County residents to get the AMA proposal on the ballot.[12]

The state paused all new irrigation in the area until after the election, stopping the growth of local agriculture.

Individual households will not be restricted because their wells are too small to meet threshold regulations,

but local farmers may need to comply with a permitting process to drill new wells.[12]

A group called Rural Water Assurance, co-founded by the president of the county farm bureau, put up billboards along I-10 urging voters to vote no on the AMA.

They also filed a lawsuit against the Douglas Basin AMA effort in June 2022, claiming that collected signature were invalid.

The lawsuit was dismissed in August.[12]

If the AMA is created, it can restrict almost all new pumping, but it can't order current users, including Riverview, to stop drawing well water.

Basing groundwater levels will continue to drop.

Residents will continue to haul water and dig new wells.

Water pumping limitations will deter new farms, further slowing the county's economy.[12]

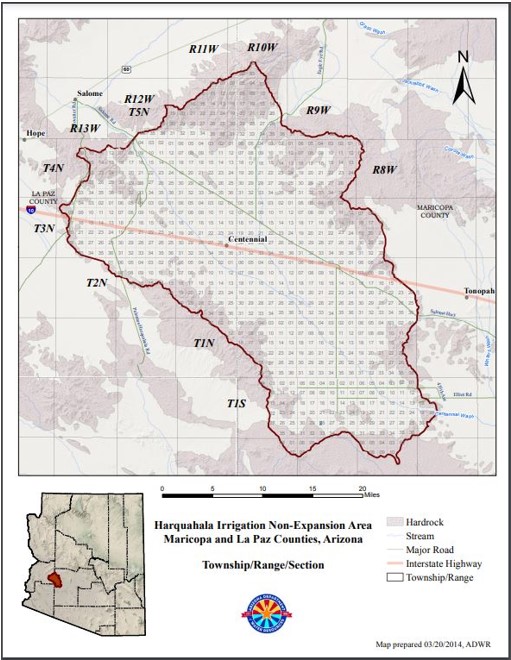

The Harquahala groundwater basin is located 60 miles west of Phoenix along I-10.

It contains approximately 766 square miles of La Paz and Maricopa counties.[20]

ADWR estimated that there are between 7 and 8-million acre-feet of water in the Harquahala aquifer.[18]

Years of anti-regulation sentiment have led to a grassroots campaign for restrictions on new wells which could restrict future corporate farming operations.[12]

Within the 1980 Groundwater Management Act

is a provision allowing rural communities to propose a ballot question about whether to establish an AMA.

If the ballot question wins a majority vote, the state then appoints a committee to supervise groundwater in the basin.

The committee can impose restrictions on new irrigation activity, limiting land area using groundwater.[12],[27],

A group called the Arizona Water Defenders wants to create a new AMA to regulate groundwater in the conservative Willcox and Douglas Basins.

They had no difficulty obtaining the required 250 signatures from Cochise County residents to get the AMA proposal on the ballot.[12]

The state paused all new irrigation in the area until after the election, stopping the growth of local agriculture.

Individual households will not be restricted because their wells are too small to meet threshold regulations,

but local farmers may need to comply with a permitting process to drill new wells.[12]

A group called Rural Water Assurance, co-founded by the president of the county farm bureau, put up billboards along I-10 urging voters to vote no on the AMA.

They also filed a lawsuit against the Douglas Basin AMA effort in June 2022, claiming that collected signature were invalid.

The lawsuit was dismissed in August.[12]

If the AMA is created, it can restrict almost all new pumping, but it can't order current users, including Riverview, to stop drawing well water.

Basing groundwater levels will continue to drop.

Residents will continue to haul water and dig new wells.

Water pumping limitations will deter new farms, further slowing the county's economy.[12]

The Harquahala groundwater basin is located 60 miles west of Phoenix along I-10.

It contains approximately 766 square miles of La Paz and Maricopa counties.[20]

ADWR estimated that there are between 7 and 8-million acre-feet of water in the Harquahala aquifer.[18]

In October 2022 the city of Queen Creek paid $30 million for 500,000 acre-feet of Maricopa and La Paz county water rights for that water.

The city plans on using 5,000 acre-feet per year for the next 100 years.

The sellers are part of the Harquahala Valley Water Association and will move the water through the CAP canal.[18]

On November 8, 2022, Cochise County residents approved Proposition 422 to establish an AMA in the Douglas Basin, joining 82% of Arizona where groundwater is managed by an AMA.

Voters rejected a measure by a 2-to-1 margin to create a similar management area in the Willcox Basin, where groundwater withdrawal will remain unregulated.[14]

In January 2023 the city of Buckeye agreed to pay $80 million for an acre of Harquahala Basin and its water rights.

The purchase allows Buckeye to use 5,926 acre-feet per year for the next 100 years.[19]

In 2023 Arizona state attorney general Kris Mayes accused ADWR of failing to protect groundwater,

by ignoring its responsibility to study the need for new AMAs.

The Saudi firm Fondomonte has been pumping groundwater to grow alfalfa in La Paz county to feed Saudi cattle.

Mayes promised to cancel the Saudi lease and stated that the use of Arizona's groundwater by the Saudis is illegal,

but governor Hobbs said the cancellation is not legally possible.

Mayes successfully managed to get the state land department to cancel two requests by the Saudis to drill two additional wells in La Paz county.[17]

In June 2023 ADWR released an updated model of groundwater conditions in the Phoenix AMA, consisting of 5,646 square miles and 4.6 million residents.

The results showed that over the next 100 years that AMA will have 4.86 million acre-feet of

unmet demandoccurs when groundwater can no longer be pumped from a well at the modeled rate due to aquifer depletion

for groundwater supplies under current conditions.[22]

As a result of the study the State will no longer approve new determinations of assured water supply within the Phoenix AMA based on groundwater resources.

Developments within existing assured water supply certificates may proceed, but new developments will need to demonstrate that they meet required future

water supplies base on other water resources.[22]

In October 2023, Republicans in the Arizona senate were pointing fingers at each other, stalling water bills and

claiming that liberal agendas were taking away water use freedoms.

As western Arizona groundwater supplies continue to be depleted by new farms, senators still can't agree how to protect water sources in rural counties.[29]

In November 2023 the Bipartisan Water Policy Council submitted water recommendations to Governor Katie Hobbs.

They recommended closing loopholes to protect water consumers, improve Arizona's Assured Water Supply Program and reforming groundwater management policies

in rural Arizona.[30]

Under the new policy the state would have more flexible ways to protect rural groundwater decided by management plans based on the needs of specific geographic areas.[31]

In the spring of 2024, ADWR's Field Services team began collecting water-level measurements in the Virgin River, Grand Wash, Shivwits Plateau, Kanab Plateau,

Paria, and Coconino Plateau groundwater basins. A survey conducted in 1976 by the USGS collected data from Grand Wash, Shivwits Plateau, Kanab Plateau,

Paria Basins. A Virgin River Basin survey was conducted in 1991 and Coconino Plateau Basin survey in 2004.[32]

The northwestern Arizona basin sweep covers an area from the Virgin River, Virgin River Mountains, Grand Canyon, east to Paria Canyon and southeast to the

Colorado River region west of Page to the San Fransisco Mountains just northwest of Flagstaff.[32]

The basin sweep measures water levels at hundreds of groundwater basin wells. The data will be used to analyze water trends, create groundwater models, maps,

and hydrology reports used for water planning and management.[32]

The University of Arizona Project WET provides nine short videos on groundwater storage, pumping, reuse and conservation[7]

and the ASU Kyl Center for Water Policy has an app which the public can use to track Arizona's groundwater level changes.[9]

Sources:

[1]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (n. d.). AZ's Groundwater Management Act Of 1980.

https://new.azwater.gov/news/articles/2016-18-11

[2]

Paul, H. (Oct. 2, 2018). 10 things you should know about Arizona's Groundwater Management Act. Audubon Society.

https://www.audubon.org/news/10-things-you-should-know-about-arizonas-groundwater-management-act

[3]

Allhands, J. (May 13, 2019). What you don't know about the water law that saved Arizona. The Republic.

https://www.azcentral.com/story/opinion/op-ed/joannaallhands/2018/01/04/lessons-groundwater-management-act-saved-arizona/1000061001/

[4]

Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District. (n. d.). Welcome to CAGRD.

https://www.cagrd.com/

What are Arizona's five AMAs?

[5]

Salt River Project. (2017). The Story of SRP: Water, power, and community.

https://www.srpnet.com/about/history/StoryofSRP_HistoryBook.pdf

[6]

Carruth, R. L., et al. (2018). Groundwater-storage change and land-surface elevation change in Tucson Basin and Avra Valley, South-Central Arizona-2003-2016. USGS.

https://pubs.usgs.gov/sir/2018/5154/sir20185154.pdf

[7]

University of Arizona Project WET. (2022). Arizona groundwater.

https://www.gw.projectwet.arizona.edu/groundwatervideos

[8]

Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District. (n. d.). CAGRD membership locator.

https://library.cap-az.com/maps/cagrd/membership-locator

[9]

Kyl Center for Water Policy. (n. d.). Groundwater level tracker.

https://asu.maps.arcgis.com/apps/webappviewer/index.html?id=40ab99d10a224d6c83818fb0e1c153e0

Where does the Central Arizona Project begin?

[10]

Arizona Water Banking Authority. (n. d.). History.

https://waterbank.az.gov/about-us/history

[11]

Person, D. (Oct. 17, 2022). How does the Colorado River shortage affect CAGRD supplies? Know Your Water News. Central Arizona Project.

https://knowyourwaternews.com/how-does-the-colorado-river-shortage-affect-cagrd-supplies/

[12]

Bittle, J. (Oct. 25, 2022). The Cochise County groundwater wars. Grist.

https://grist.org/regulation/arizona-groundwater-cochise-county-riverview/?utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter&utm_campaign=weekly

[13]

Schneider, K. (Mar. 17, 2022). Arizona faces a reckoning over water. High Country News.

https://www.hcn.org/articles/water-arizona-faces-a-reckoning-over-water

[14]

Frederico, J. (Nov. 10, 2022). Cochise County voters approve one groundwater management plan, reject another. Arizona Republic.

https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/politics/elections/2022/11/10/cochise-voters-approve-one-groundwater-plan-reject-another/8319272001/

[15]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (Jan. 20, 2023). ADWR releases much-anticipated Hassayampa sub-basin groundwater model.

https://new.azwater.gov/news/articles/2023-20-01

[16]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (Mar. 15, 2023). ADWR field researchers launch a northwestern Arizona "basin sweep."

https://new.azwater.gov/news/articles/2023-15-03

[17]

Fisher, H. (Apr. 21, 2023). Attorney general: Arizona agency failing to protect groundwater. tucson.com.

https://tucson.com/news/local/subscriber/attorney-general-arizona-agency-failing-to-protect-groundwater/article_0bb2366c-e084-11ed-b5a5-f7ed6de30711.html#:~:text=PHOENIX%20%E2%80%94%20State%20Attorney%20General%20Kris,its%20job%20to%20protect%20groundwater.

[18]

Moran, M. (Oct. 3, 2022). QC inks another big water deal to meet town needs. Queen Creek Tribune.

https://www.queencreektribune.com/news/qc-inks-another-big-water-deal-to-meet-town-needs/article_c4ed9aa6-40ff-11ed-9c64-271fcb159d4f.html#:~:text=Queen%20Creek%20has%20taken%20the,Paz%20counties%20for%20%2430%2Dmillion.

[19]

Myskow, W. (May 6, 2023). Amid continuing drought, Arizona is coming up with new sources of water--If cities can afford them. Inside Climate News.

https://insideclimatenews.org/news/06052023/arizona-water-sources-drought/

[20]

Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. (n. d.). Ambient groundwater quality of the Harquahala Basin: A 2009-2014 baseline study - June 2014.

https://static.azdeq.gov/wqd/gw/fs/14-09_harquahalabasin_fs.pdf

[21]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (2023). Active management areas.

https://new.azwater.gov/ama#:~:text=Irrigation%20Non%2DExpansion%20Areas%20(INAs,Hualapai%20Valley%20INA%20in%202022.

[22]

Arizona Department of Water Resources. (2023). Phoenix AMA groundwater supply updates.

https://new.azwater.gov/phoenix-ama-groundwater-supply-updates

[23]

Water Resources Research Center. (2023). Transboundary aquifer assessment program.

https://wrrc.arizona.edu/programs/taap-transboundary-aquifer-assessment-program

[24]

U.S.G.S. (Dec. 27, 2017). Transboundary aquifer assessment program (TAAP).

https://webapps.usgs.gov/taap/

[25]

Arizona State Legislature. (2023). 45-411. Initial active management areas; maps. Title 45.

https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https://www.azleg.gov/ars/45/00411.htm

[26]

Arizona State Legislature. (2023). 45-411.02. Modification of boundaries of Tucson active management area; map. Title 45.

https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.azleg.gov%2Fars%2F45%2F00411-02.htm

[27]

Arizona State Legislature. (2023). 45-415. Local initiation for active management area; procedures. Title 45.

https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https://www.azleg.gov/ars/45/00415.htm

[28]

Arizona State Legislature. (2023). 45-431. Initial irrigation non-expansion areas. Title 45.

https://www.azleg.gov/viewdocument/?docName=https://www.azleg.gov/ars/45/00431.htm

[29]

Flesher, H. (Oct. 21, 2023). Arizona lawmakers lash out at colleagues for preventing groundwater regulation. Arizona Daily Star.

https://tucson.com/news/local/subscriber/arizona-groundwater-pumping-rural-farms-legislators/article_82390526-6f78-11ee-a75c-0b16a29e28a0.html#:~:text=Arizona%20lawmakers%20lash%20out%20at%20colleague%20for%20preventing%20groundwater%20regulation,-Howard%20Fischer&text=How%20to%20regulate%20groundwater%20use,an%20issue%20dividing%20Republican%20legislators.&text=Upset%20with%20what%20he%20said,to%20protect%20groundwater%2C%20the%20No.

[30]

Office of the Governor Katie Hobbs. (Nov. 29, 2023). Governor Hobbs' bipartisan water policy delivers critical recommendation to protect Arizona's water security.

https://azgovernor.gov/office-arizona-governor/news/2023/11/governor-hobbs-bipartisan-water-policy-council-delivers

[31]

Muskow, W. (Dec. 19, 2023). Rural Arizona has gone decades without groundwater regulations. That could soon change. Inside Climate News.

https://insideclimatenews.org/news/19122023/rural-arizona-decades-without-groundwater-regulations/

[32]

State of Arizona. (Mar. 14, 2024). Out in the field: ADWR hydrologists conducting "basin sweep" in vast northwest region.

https://www.azwater.gov/news/articles/2024-03-13

In October 2022 the city of Queen Creek paid $30 million for 500,000 acre-feet of Maricopa and La Paz county water rights for that water.

The city plans on using 5,000 acre-feet per year for the next 100 years.

The sellers are part of the Harquahala Valley Water Association and will move the water through the CAP canal.[18]

On November 8, 2022, Cochise County residents approved Proposition 422 to establish an AMA in the Douglas Basin, joining 82% of Arizona where groundwater is managed by an AMA.

Voters rejected a measure by a 2-to-1 margin to create a similar management area in the Willcox Basin, where groundwater withdrawal will remain unregulated.[14]

In January 2023 the city of Buckeye agreed to pay $80 million for an acre of Harquahala Basin and its water rights.

The purchase allows Buckeye to use 5,926 acre-feet per year for the next 100 years.[19]

In 2023 Arizona state attorney general Kris Mayes accused ADWR of failing to protect groundwater,

by ignoring its responsibility to study the need for new AMAs.

The Saudi firm Fondomonte has been pumping groundwater to grow alfalfa in La Paz county to feed Saudi cattle.

Mayes promised to cancel the Saudi lease and stated that the use of Arizona's groundwater by the Saudis is illegal,

but governor Hobbs said the cancellation is not legally possible.

Mayes successfully managed to get the state land department to cancel two requests by the Saudis to drill two additional wells in La Paz county.[17]

In June 2023 ADWR released an updated model of groundwater conditions in the Phoenix AMA, consisting of 5,646 square miles and 4.6 million residents.

The results showed that over the next 100 years that AMA will have 4.86 million acre-feet of

unmet demandoccurs when groundwater can no longer be pumped from a well at the modeled rate due to aquifer depletion

for groundwater supplies under current conditions.[22]

As a result of the study the State will no longer approve new determinations of assured water supply within the Phoenix AMA based on groundwater resources.

Developments within existing assured water supply certificates may proceed, but new developments will need to demonstrate that they meet required future

water supplies base on other water resources.[22]

In October 2023, Republicans in the Arizona senate were pointing fingers at each other, stalling water bills and

claiming that liberal agendas were taking away water use freedoms.

As western Arizona groundwater supplies continue to be depleted by new farms, senators still can't agree how to protect water sources in rural counties.[29]

In November 2023 the Bipartisan Water Policy Council submitted water recommendations to Governor Katie Hobbs.

They recommended closing loopholes to protect water consumers, improve Arizona's Assured Water Supply Program and reforming groundwater management policies

in rural Arizona.[30]

Under the new policy the state would have more flexible ways to protect rural groundwater decided by management plans based on the needs of specific geographic areas.[31]

In the spring of 2024, ADWR's Field Services team began collecting water-level measurements in the Virgin River, Grand Wash, Shivwits Plateau, Kanab Plateau,

Paria, and Coconino Plateau groundwater basins. A survey conducted in 1976 by the USGS collected data from Grand Wash, Shivwits Plateau, Kanab Plateau,